|

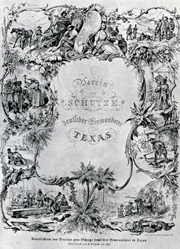

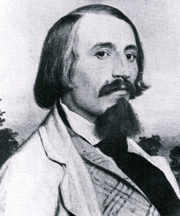

Wilhelm Reuter was the first of our ancestors to come to America. As a young single man he signed on with a group of German noblemen who hoped to colonize the then-Republic of Texas. He sailed off in 1844, expecting to take possession of the 160 acres of prime land he had been promised. The star-struck young adventurer surely had no idea what was in store for him. Wilhelm was born to a prosperous family in Schweinfurt, Bavaria, the fifth of six children. His father, Martin Wilhelm, was an attorney and city councilor. Wilhelm attended the Gymnasium Academicum, where he studied Latin and other classical subjects. He loved music, singing in choral groups and playing an instrument — possibly a button accordion. The social life of young people of his class revolved around choral societies such as the Liederkranz, which held elaborate costume parades on the town square. Wilhelm probably participated in the 1840 extravaganza there that included an elephant and a zebra. By the time he set out for Texas at age 24, Wilhelm spoke both English and French. He may well have attended university and/or traveled outside of Germany, as did his father and at least one brother. The ship’s log lists his occupation as Merchant (Kaufmann). We can only speculate about why the young man decided to strike out on his own. Most nineteenth century immigrants from Germany came to the new world seeking economic relief, freedom from political oppression, or adventure — or some combination of the three. Wilhelm did not suffer the dire economic straits that compelled most of our ancestors to leave Germany, though he did face shrinking opportunities and a declining standard of living. We have no evidence that he shared the revolutionary sentiments of some of his contemporaries; in fact, we know nothing about his political convictions. But his older sister Caroline hinted at a measure of political idealism — along with high optimism — in a letter written in 1846: “...accompanied by our most fervent blessings, he left his home town, his mother and siblings, to seek a new fatherland to which he committed himself, sight unseen, with youthful enthusiasm.” It seems likely that Wilhelm, the third son in his family, crossed the ocean to seek adventure and fortune. He may have read earlier settlers’ accounts of the fabled territory of Texas with its abundant game, forests, and savannahs. Perhaps the recent death of his ultra-conservative father — whose youthful sojourn in France had resulted in disgrace— freed Wilhelm to pursue his own wanderlust. The offer of land was made by the Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas (Verein zum Schutze deutscher Einwanderer in Texas). A group of German noblemen founded the Society in 1842, expecting to reap influence and profits from future trade with the German colony they would create. The Verein planned to purchase a large tract of land and deed sizable parcels to its members under contracts that also promised comfortable ship’s passage, ground transportation, and all the tools and supplies necessary to make a new life on the frontier. Wilhelm was to sail on their very first voyage. The Society’s Chief Engineer, Nicholas Zink, wrote to the Directors of the Society after meeting him: “I hereby note that a Herr Reuter will be applying. He is a man of some means, speaks English and French, and will be very useful in this regard. He is quite a capable young man.” Wilhelm and a hometown comrade named Christoph Luck sailed from Bremerhaven in September 1844 aboard the Johann Dethardt, a two-masted sailing brig. They had smooth seas and good winds for most of their two-month crossing. But the passengers had to endure an uncivil crew and substandard provisions — perhaps the first sign that the Society would not make good on its ambitious promises. They were only too happy to reach the port of Galveston in late November and disembark for a good meal and the next stage of their adventure. They waited a week for small schooners to ferry them from the island of Galveston to Port Lavaca, a handful of houses 140 miles down the coast on Matagorda Bay. Verein officials met the settlers there and took them inland to a small woods with a creek, where they camped in tents. They settled in to await the arrival of their leader, Prince Carl von Solms-Braunfels, and three more ships bringing the rest of their party. Prince Solms, the General Commissioner of the Society, had been in Texas for six months attempting to solve the thorny logistical problems of settling hundreds of Europeans on the Texas frontier. So far he had discovered that the Verein’s land lay in unexplored wilderness deep in Comanche territory; that equipment and supplies for transport were inadequate; that roads were non-existent; that Verein funds were being rapidly depleted; and that the local agents acting on his behalf were incompetent, corrupt, or both. The prince kept these concerns to himself when he arrived at the immigrant camp in December. In his princely regalia he was an impressive sight to the settlers, most of whom had never had any contact with royalty. The Germans treated the prince with great deference. The Texians had their doubts. The prince’s dress and the strict military discipline he exacted from his aides provoked amusement in Galveston. A Mrs. Maverick wrote: “He and his attendants had plumes on their hats, and it did not seem to me that they were the most suitable personalities for the hardships of frontier life....The prince aroused in us the feeling [that] he would not be sure of himself outside among the cattle...” But the prince took charge of matters. He made plans to move the Germans inland, establishing a series of camps as way stations. He formed a colonial council, organized a militia, hired a pastor for his flock, pressed for supplies, and reprimanded or dismissed subordinates as needed. |

Click on pictures to enlarge

Wilhelm Reuter  “Liederkranz” costume parade in Schweinfurt, 1840  Romanticized image of life in Texas  Advertisement for the Society for the Protection of German Emigrants  A two-masted sailing brig  Galveston in 1846  Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels |

|||

|

By Christmas Wilhelm and his shipmates had been in camp for a month. Although the Society provided plenty of food, there was little to do except cook it and go hunting. Immigrants from the other three ships were camped at Indian Point —renamed Carlshafen —where the prince had quickly bought land for that purpose.

On the morning of December 24, Prince Solms chose four young men, one of them Wilhelm, to ride with him and two senior officials to the second camp four hours away. There the prince received a joyous welcome. Their party returned by boat later that day and walked from the bay back to camp by the light of a full moon to celebrate their first Christmas in the new world. Since there were no evergreen trees to be found, the prince had an oak tree decorated with lighted candles and gifts for the children. On January 1, 1845, the colonists began their trek inland, joining forces at Agua Dulce, or Chocolate Creek. Of the approximately 300 settlers, 128 were men. Prince Solms organized a militia of 20 men for protection. One writer described the soldiers of the Society as follows: “The neat young fellows in their high riding boots, their gray woolen blouses with black velvet collars and brass buttons, their cocked-hats with the long black feather, with their swords strapped on and armed with a good rifle, made a good impression.” The immigrants proceeded slowly, in two groups, traveling by horseback, wagon, oxcart, or on foot from one newly established camp to the next: Victoria, McCoy’s Creek, Gonzales and Seguin. Their route roughly followed the Guadalupe River. The hunters among them delighted in the great herds of wild game feeding on the prairie: deer, geese, ducks, wild turkeys and “prairie chickens” (large grouse). At farming homesteads along the way they were met with hospitality and gifts of milk, eggs, and bread. They also encountered their first Native Americans, described by one German as “the loathsome Tonkawa clothed in animal skins.” It took two months to cover the 80 miles from Lavaca to Mc Coy’s Creek. From there Prince Solms rode to San Antonio to purchase a tract of land at Comal Springs on the Guadalupe. He had confirmed that the original tract was uninhabitable, and he needed a place to settle his colonists. The company pressed on, making the 56 miles to Seguin in two weeks. There they met the prince and continued 10 more miles along the river. |

The Prince's Christmas tree  The long trek inland  Camping en route |

|||

|

On March 21, 1845, the prince led fifteen wagons across the Guadalupe to the site of their new home. It was a good tract with ample protection afforded by the confluence of Comal Springs, the river, and a hillside palisade. Wilhelm was part of that first party of 200 who founded New Braunfels on that wintry Good Friday.

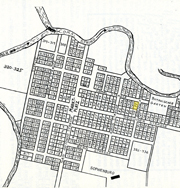

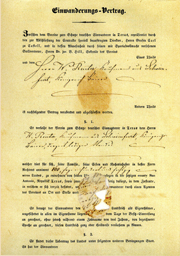

As soon as the land could be surveyed, a drawing was held to distribute the town and farm lots. Each head of family and single man received a half-acre town lot and a 9 1/2-acre farm lot. Wilhelm Reuter drew Town Lot #88 and Acre Lot #53. The settlers began to cut and hew logs to build shelters or cabins. Although many had no experience with such work, they learned from each other and by doing. The weather was rainy and cold, and the food supply problematic. There was plenty of meat and game, but grain was lacking; the huge supply of corn in the temporary warehouse had been ruined thanks to a leaky roof. Some colonists went to work clearing their farm lots and planting corn and potatoes. We do not know if Wilhelm ever planted anything on his farm lot. He did erect a cabin on his town lot. And he became a member of the Protestant church: his was the 21st name on Rev. Ervendberg’s s enrollment list of 305 members. In late April, Prince Solms held a cornerstone-laying ceremony for a fortress he planned to erect on a hill overlooking the settlement. Lacking a German flag, he raised the Austrian colors. This displeased many of the colonists, who felt they had left the old country behind and cast their lot with the new. Taking matters into their own hands, they hoisted the Texas flag in the plaza. Shortly thereafter the prince, having completed his mission, departed for his castle in Braunfels. He never returned to Texas. Hermann Seele arrived in the new settlement in May. Seele, who would become the schoolteacher, kept a diary and later wrote an account of life in the early days, in which he noted: Some of the first colonists received oxen, plows, and carts from the society. Every day all were given fresh meat, corn, and other provisions when available. They had to grind the corn themselves with hand mills attached to trees... The settlers helped one another by sharing their possessions and skills and developed a lively social life. In the evening the cheery German songs rang out as the soldiers of the society marched singing through the streets. Messrs. Reuter, Bauer, Herbst, Theilepape and Rennert organized a quartet that met in Reuter’s cabin. But most colonists regarded New Braunfels as a temporary settlement. They still expected to occupy the 160 and 320-acre tracts specified in their Verein contracts. Some were highly critical of the Verein and refused to become self-sufficient, claiming the Society had pledged to support them, while others embraced life in New Braunfels and worked hard to build livelihoods in farming or trades. The Christmas holidays found Wilhelm in New Braunfels, working and making merry with friends, including Seele, who had also become the unofficial assistant to the pastor. Seele wrote the following entry in his diary: Sunday evening, December 28, 1845: The Christmas holidays passed bright and pleasant under green boughs... On the second day of Christmas I was in a cheerful mood. I had dinner at the Ervendbergs’. I didn’t really want to stay, but I couldn’t refuse the invitation, since the pastor’s wife was still miffed about our absence on Christmas Eve....Reuter stayed until late and played and sang. Reuter had his meals with us these two days, and on Saturday he returned to work. Celebrating his second Christmas in Texas, Wilhelm was probably unaware of the tragedy that had struck his family in Schweinfurt four months earlier. Letters to and from Germany were at least two months in transit, but this did not explain the lapse in communication that would span almost a year. Shortly after his arrival in New Braunfels in the spring, Wilhelm had written two letters to his family. According to his sister Caroline, he had established himself in the new community and was enjoying excellent health. He was enthusiastic about the beauty of the land, “the infinite riches of nature, and the climate, so agreeably mild due to the pleasant breezes.” She added: “Oftentimes he enjoyed the honor of being in the presence of His Highness Prince Solms Braunfels, and I venture to say that perhaps His Highness would still remember him.” He had some complaints about the Verein but remained optimistic that things would improve. He also asked his family to send him the sum of 500 gold florins (about $2,000). But in August Wilhelm’s mother and two sisters in Schweinfurt came down with fever. Caroline recovered, but his mother and younger sister Marianna Theresa died within a few weeks of each other. Their mother’s estate, including the family home, was locked in probate and could not be distributed without Wilhelm’s signature. No one had thought to get a power of attorney. Wilhelm’s older brother Gustav wrote several letters in the following months, sending one via the Society’s banker along with a draft for the 500 gold florins. His younger brother Emil also wrote from England. But eight months passed without any reply from Wilhelm. In April 1846 Gustav Reuter finally wrote to the General Management of the Verein in Germany seeking information about Wilhelm’s whereabouts and health. He enclosed yet another letter to Wilhelm, asking that it be delivered to Texas. Caroline Reuter penned her own inquiry to Verein officials on July 28. Longer and more personal than her brother’s correspondence, her letter poured out her anguish and fear for Wilhelm’s safety: “You can well imagine the endless anxiety we feel about this brother who is so very far away from us, and particularly how painfully affected we are by the recent distressing news coming out of Texas.” She was referring to the terrible epidemics of fever that had decimated the second wave of immigrants. “We would like to be granted some reassurance that at this time we can still count him among the living.” She begged for the “highly esteemed Society’s kindness and forbearance toward the unpracticed pen of a lady.” She too enclosed a letter for Wilhelm. She received a reply claiming the rumors from Texas were false and enclosing a reprint of a recent colonist’s letter with more “gratifying news,” but containing no information about Wilhelm. What explained the yearlong silence at such a critical time for the Reuter family? The Society’s financial difficulties were undoubtedly to blame. By the fall of 1845 the Texas organization was in dire financial straits, with more than $20,000 in debts and zero cash on hand. Three thousand new immigrants were due to arrive in the coming months, all needing to be fed, housed, and transported. Settlers in New Braunfels who had entrusted their life savings to the Society for safekeeping before leaving Germany found their personal funds frozen and used by desperate Verein officials, who continued to buy food and supplies on credit while waiting for promised cash infusions from the parent organization in Germany. Verein records indicate that the bank draft in Wilhelm’s name was received in New Braunfels on October 4, 1845 and entrusted to a Col. Davis on November 8, at which time a receipt was dispatched to the banker in Frankfurt. Yet Wilhelm himself did not receive the money. And news of the receipt had not reached Schweinfurt by July of the following year. Most likely the Society used Wilhelm’s 500 florins as it had used its other depositors’s funds — to meet current expenses. Might it also have withheld the letters his family sent, or perhaps detained letters Wilhelm wrote back to Germany? How else can the absence of news in Schweinfurt be explained? When John O. Meusebach took over as Commissioner General of the Verein in Texas, he made it his mission to restore fiscal integrity and to meet the Society’s obligations to its members. In July 1846, almost a year after the bank draft was dispatched from Frankfurt, Meusebach responded to the inquiry from headquarters in Germany indicating that Wilhelm had received his money. We do not know when he received news of his mother’s and sister’s deaths, nor how the estate was settled, nor when his siblings finally learned that he was still alive. |

The Guadalupe River  New Braunfels town lots of 1845  Protestant Church, built in 1846  Hermann Seele  Accordion belonging to Wilhelm Reuter’s grandson  Cedar Christmas tree with German ornaments  An early log cabin in New Braunfels  A 19th century gold florin  ‘...the unpracticed pen of a lady...’  Wilhelm's contract with the Verein  John Meusebach |

|||

|

From this point on we have no record of Wilhelm’s whereabouts or activities until March 1852 — a six-year gap. We can only speculate about where was he and what was he doing.

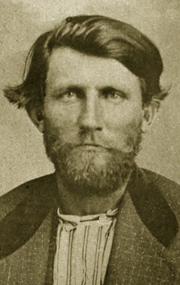

It is likely that Wilhelm experienced disillusionment and anger at the Society for withholding his money and perhaps his family correspondence. He may also have been dissatisfied with his 10 acres of land in lieu of the 160 he expected. Perhaps he reacted by leaving New Braunfels to go adventuring with his hometown friend Christoph Luck or another companion for some part of the period from 1846 to 1851. He was young and unattached, with money in his pocket and no particular reason to settle down. He might have attempted to reach the Verein land grant, or headed to Fredericksburg or another new settlement. He may even have returned to Germany to settle his mother’s estate.. His whereabouts in 1850 is a mystery, as his name does not appear in the New Braunfels census or in any other Texas census. If he did stay in town he seems to have accomplished little. He failed to pay taxes on his town lot for the years 1846-1849 — whether because of absence, disinterest, pique, or lack of funds, we do not know. In 1850 it was sold at public auction to one Gustavus Heusinger for $10.48, plus back taxes of $8.98. Wilhelm still owned a 9 1/2-acre lot outside of town; after 1850 he either lived on that land or boarded elsewhere in New Braunfels. There are indications he may have acquired a somewhat shady reputation during that time. Two entries in the diary of Elise Tips Wuppermann make less-than-glowing reference to Wilhelm. In early 1852 Elise wrote about a trip to New Braunfels with her husband Otto: “There was a concert the evening of [February] 24th. I had intended to sing a duet with Herr Reuter, but since Otto found [the prospect] upsetting, I declined.” From this we learn that Wilhelm was still singing; that he was active in the social life of New Braunfels; and that one husband found the prospect of a public duet with his respectable wife distasteful. Elise was a first cousin of Wilhelmine Tips, who would become Wilhelm’s wife. Known as Minchen to her family, she had come to Texas in early 1849 and been widowed twice in tragic short order. In March 1853 Elise received a letter from Minchen and noted in her diary: “...she wants to marry for a third time, and has become engaged to Wilhelm Reuter. How is it possible?” Despite Elise’s s evident disapproval, Wilhelm, age 33, married Wilhelmine Carolina Tips Heusinger, 30, on March 19, 1853. His bride was a woman of some means, with assets of at least $550. Wilhelmine held a $300 mortgage note from her cousin Emil von Stein, which he repaid in 1854. She also inherited her second husband Gustav Heusinger’s farm, the sale of which netted her $248. Wilhelm had sold his farm lot for $70 and his original land grant for $100. The newlyweds started out with a sizable nest egg. By the time their first child, Marie Caroline, was born a year later, they were living in Medina County. In 1856 Wilhelm Reuter purchased a tract of land on the east side of the Seco Creek for $110. The following year he bought more land on the west bank of the Seco for $400. The land was a mile and a half west of D’Hanis, in an area called Fort Lincoln. It was here that the couple settled to raise a family. Their second daughter, Alice Henriette, was born in 1858. Wilhelm and Wilhelmine lived in a small two-room house at first. Later they built a large two-story house of white stone quarried from the area, which became known as ‘Casa Blanca.’ It served as an inn for travelers en route to and from Mexico. According to family legend, one guest was driving a herd of camels across the country to be tried in the Arizona desert, and gave the Reuters’s small daughters a ride on one of them. Wilhelm became a successful cattle rancher. His two brands are still on record in Medina County. We have few specific details about the Reuters’s life on their land —only memories handed down the generations. Their granddaughter Mimmi Richter Schweers related the story of a brush with Comanches: “One evening when Wilhelm was bringing in the horses, Wilhelmine stood watching him from a bluff overlooking the valley. She noticed tiny objects hopping from bush to bush. She screamed as loud as she could. When Wilhelm heard her, he went home to see what was wrong. The next day he found the horses shot with arrows.” And Alice recalled how her father and mother made yellow cheese: “Papa saved the little stomach from the calf when he killed it, and they would hang it out to dry without washing it. After it was dry, they put it in a bottle of water and then they would use that water to make the cheese with. Oh my, it was fine cheese.” Wilhelm also knew, or learned, basic carpentry. Among other things, he built a small, sturdy oak cabinet that stands in my office today. He continued to sing in choral societies whenever he could, attending statewide Sängerfeste (choir festivals) in San Antonio. The family prospered on their ranch. The 1860 census indicates that Wilhelm held real estate valued at $1,700 and a personal estate valued at $3,274. In addition to the family, three others were listed as members of the household: Innocente Gomez, a 15-year-old native of Mexico, identified as a servant; Willam Foster, a 25-year old hostler from New York, and May Waidena, a native of Prussia. Wilhelm and Wilhelmine wanted their daughters to be well educated. They planned to send them to boarding school in San Antonio when they were old enough. The Civil War changed those plans, and all of their lives. In 1861 Texas joined the Confederacy. The Union army withdrew from Texas, leaving frontier forts undefended against hostile Indians. The Union navy blockaded gulf ports, causing the economy to suffer and prices to rise. There were shortages of cloth, shoes, paper, medicines, and other basic supplies. Over time, the war brought hardship and privation to previously prosperous families. We do not know how Wilhelm felt about the Confederacy. Many of his friends and fellow Germans opposed slavery. Some, including Theo Goldbeck, had fled to Mexico following their outspoken public declarations and the Know-Nothing reprisals that followed. But most German immigrants, regardless of their personal beliefs, went along with the government in power and fought for its cause. By 1863, every able-bodied man between the ages of 17 and 45 was eligible for conscription. It was probably with scant eagerness that Wilhelm left his wife, two small daughters, and ranch to become a soldier. He was 43 when he was mustered into the Confederate States Provisional Army in Castroville. Four days later, on October 10, 1863, Wilhelm Reuter died of a fever, the result of a stomach or intestinal disorder. Oral family history suggests that Wilhelm’s s illness was not a sudden one. His granddaughter Mimmi Schweers wrote that “after a trip to Mexico [he] took sick, even went to San Antonio to Doctors, could not help him [sic].” His daughter Alice said, “...even while Papa was sick, we helped to do the work...” Both references indicate that Wilhelm suffered from a prolonged illness prior to his conscription, during which time he was unable to work. Wilhelmine was left a widow for the third time. In her Stammbuch, she mourns the death of “my dear beloved, Wilhelm, our most deeply loved, unforgettable Papa.” Wilhelm Reuter was buried in a family cemetery near his home. © Julia Moore, 2015. All rights reserved. Related Stories: Wilhelmine Tips Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas German Emigration in the Nineteenth Century The Voyage of the Johann Dethardt New Braunfels Martin Wilhelm Reuter Schweinfurt Sources: Solms-Braunfels Archives, New Braunfels, Texas Biesele, Rudolph, The History of the German Settlements in Texas, German-Texan Heritage Society, 1987 Fey, Everett Anthony, New Braunfels: The First Founders, Eakin Press, Ausin, Texas, 1994 Seele, Hermann, “Meine Ankunft in New Braunfels,” in Kalendar der Neu Braunfelser Zeitung für 1914 Seele, Hermann, The Cypress and Other Writings of a German Pioneer in Texas, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1979 The Diary of Hermann Seele, German-Texan Heritage Society, 1995 Texanische Tagebücher 1850-1865, (The Diary of Elise Wuppermann née Tips) ed. Gerhard Vowinckel, Hamburg, 2013 Medina County Land Records, Vol. 5 The History of Medina County, Texas, Dallas, Texas, National Sharegraphics, Inc. Stammbuch of Wilhelmine Tips Reuter |

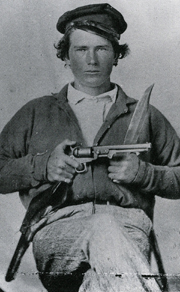

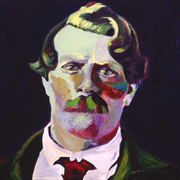

The lure of the hill country  Saloon in New Braunfels  Germania singing society  Wilhelm Reuter  Seco Creek  Wilhelm Reuter's cattle brand  Chest made by Wilhelm Reuter  Medina County ranchland  A Texas confederate soldier  “Wilhelm,” painting by Julia Moore |