|

||||

|

One of the stranger episodes in the colorful history of Texas involved the ambition of a handful of German royals to turn the then-republic into a major trading partner, if not a full-fledged German colony. To this end they sent thousands of their citizens to Texas in the 1840s to establish large-scale settlements. The nobles’ old-world ideals, poor planning, and inadequate funding soon ran headlong into the raw reality of the frontier. The result was a lively adventure — or tragic fate — for the settlers who had signed on with the venture.

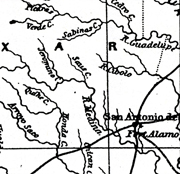

The Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas (Verein zum Schutze deutscher Einwanderer in Texas) was founded by about 20 princes and counts. It quickly became known as the Adelsverein (Society of Noblemen) or simply the Verein. At their initial meeting in April 1842, the noblemen resolved to purchase a tract of land in Texas, and immediately dispatched two of their number to the republic for that purpose. Prince Victor of Leiningen met with Sam Houston, President of the Republic, to try to secure a colonization land grant and tax concessions, but came up empty-handed. Meanwhile Count Joseph of Boos-Waldeck scouted for land. He failed to find a suitable tract, but purchased a small plantation for the Society’s headquarters in Fayette County, near the existing German settlements of Industry and Round Top. The count stayed in Texas for over a year; but upon his return he advised against the nobles’ colonization plan on the grounds that it would be prohibitively expensive. He also opposed their acquiring an existing colonization contract being offered by one Alexander Bourgeois, whom the count termed “a swindler.” When the other members overruled him on both counts, Boos-Waldeck severed his ties with the venture. In March 1844 the Society voted to pursue large-scale colonization. It reorganized itself into a stock company with a capitalization of $80,000 (20,000 florins), to be led by Count Carl Castell. Its stated purposes were philanthropic: to improve the conditions of the working class, open markets for German goods, and develop maritime commerce. But the nobles made careful provision for the distribution of the profits they clearly expected to realize. With virtually no advance planning or budgeting — and without securing any land in Texas — the Society launched its ambitious program to send 10,000 German families to Texas. From that point on things began to move at a dizzying pace. By 1844 the Republic of Texas had stopped issuing land grants. However, two Frenchman, Alexander Bourgeois and Armand Ducos, held an existing colonization contract for land on the Medina River, just north of Henri Castro’s grant. Bourgeois, who had added an aristocratic-sounding ‘d’Orvanne’ to his name, hurried to Germany when he heard about the Society’s plans. Although his contract had already expired, he convinced the nobles that with their backing the Texas government would renew it. In April the Society named Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels the Commissioner General for the colonial enterprise in Texas, and Bourgeois its Colonial Director. The two set off for Texas in May to get things ready for the colonists. Meanwhile a much larger land grant came into play. The three million-acre Fisher-Miller Grant lay well to the north between the Llano and Colorado rivers, in virtually unexplored Comanche territory. Henry Francis Fisher, a German who had come to Texas in 1833, obtained the grant with a partner in 1842. The following year Fisher made plans to explore the land, but was dissuaded by President Houston, who felt an armed party in the area would compromise his own efforts to negotiate a treaty with the Comanches. Instead Fisher got himself appointed Texas consul in Bremen, and by the spring of 1844 was in that city, recruiting hopeful settlers and trying to sell his land grant contract to the German princes. This he succeeded in doing in late June, having convinced his new partners that Bourgeois would not get the Medina grant renewed. Fisher was paid $7,600 for the rights to his contract, given voting rights in the colonial organization, and promised a share of the profits. Bourgeois and Prince Solms, en route to Texas, would not learn of this development for two months. Fisher too set out for Texas. Meanwhile the Verein lost no time soliciting emigrants via newspaper announcements and pamphlets. On June 16, 1844, a lengthy article appeared in the Mainzer Zeitung praising Texas as a destination and touting the benefits of émigrés settling together in large numbers to create ‘a German home in America’. Prospective settlers were promised a parcel of ‘good’ land, comfortable ships with plenty of wholesome food, agents in Texas to meet them, wagons for transport, and their own log house. The Society would provide warehouses filled with provisions, tools, seeds and plants; it would sell them oxen, horses, cows, hogs and sheep at favorable prices; it would build schools, churches, and a hospital. In short, the Society would provide for the emigrants’ every need. The Society announced it would transport 150 families in 1844, and that the first ship would leave in September. Single applicants were required to have a capital of $120, and heads of families $240. If single, a man would receive 160 acres of land; if married, 320. Among the first to respond to this offer was 24-year old Wilhelm Reuter, who applied in early July. Publicity about the venture elicited an outpouring of interest and opinion from the German public and press. The reaction was generally favorable, but criticism came as well. Some thought the princes had not done adequate planning, and that any group of commoners making such an offer would face far greater scrutiny. Others held that the emigrants’ safety could not be guaranteed in Texas, citing the unsavory local population, a looming war with Mexico, and the issue of slavery. The press largely supported the plan, seeing it as a solution to Germany’s overpopulation and a stimulus to future national trade and prosperity. The governments of Prussia and the other German states were silent. Although the Verein attempted to get their endorsement and financial backing, this never came to pass. Would-be emigrants were ecstatic at the prospect of making their momentous leap into the unknown under the guidance and protection of the most esteemed eminences in the land. The turnkey contracts the Verein offered freed emigrants from the need to plan, make difficult decisions, or take responsibility for the venture’s success. All that was asked of them was trust and hard work, and these they were willing to give. Like the German public at large, they had faith in the wisdom and bottomless financial resources of the noblemen backing the venture. While Society agents in Germany were busy chartering ships and signing up settlers, Prince Solms encountered the reality of Texas. Carl, Prince of Solms-Braunfels, was 32 years old, an officer in the Imperial Austrian Army, and the new Commissioner-General of the Verein in Texas. By the time he arrived in Galveston on July 1 with a retinue of three servants and two antiquated cannon, he was already pining for his fiancée, Princess Sophie of Salm-Salm, and longing to return to his ‘angel.’ But the prince took his commission seriously. He had less than five months to prepare for the arrival of the first shipload of settlers. The logistics were daunting given existing communication and travel conditions. Letters to and from headquarters in Germany took two months each way, dispatches within Texas days or weeks. Roads and trails were primitive, with no towns, inns, or even drinking water between destinations. There were rivers to ford, storms and brutal heat, vermin, mosquitoes, bad food, and the threat of hostile Indians. For a man accustomed to luxury and privilege, Texas surely engendered culture shock. Still, the prince was game. During his time on the frontier he enjoyed riding, hunting, rifle practice, and the occasional cultured person he encountered. The rest he endured for the sake of his mission. His first order of business in Houston was to buy a horse, which would carry him more than 1500 miles as he crisscrossed vast swaths of southern Texas over the next eleven months. He rode to Washington on the Brazos, the capital, to meet with government officials, who made vague promises but could not assure him the Bourgeois grant would be renewed. From there he went to Nassau Farm, the land previously purchased for the Society’s headquarters. He deemed its location too distant from the western parcel under consideration — some 170 miles over bad roads and trails — to be practical. In August Solms reached San Antonio. By this time he was well acquainted with frontier travel. The nights were the worst, as variously described by the prince in his diary: [The house] was dirty, bad, miserable. In the night children’s screams, barking dogs, and fleas. Slept on the porch. Saddle for a pillow. American tobacco, chewing and spitting.... Dinner and supper left something to be desired. The same for the night lodging. Many fleas and a hard bed. Feathers on wood. A night without comparison, mosquitoes, fleas, lice. In the saddle at 5:30. |

Click on pictures to enlarge

Insignia of the Society for the Protection of German Emigrants in Texas  Biebrich Palace in Wiesbaden, on the Rhine River  Count Carl of Castell  Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels  Sam Houston, President of the Republic of Texas  Advertisement for the Society for the Protection of German Emigrants  Wilhelm Reuter  Princess Sophie of Salm-Salm  The Guadalupe River: one of many to ford  Nassau Farm  San Antonio in 1856 |

|||

|

Thus far he had met with an enthusiastic welcome from German émigrés wishing to join his colony, as well as varying degrees of amazement from the Texians, who had never encountered European royalty and quickly doubled the price of anything his party wanted to buy. One German expatriate deplored the impression he made:

His Gustav-Adolph wardrobe, the hat with upturned brim and the rooster feather, wide shirt collars of bleached linen, large fencing gloves, long cavalry saber, and, not least, the gigantic hip boots, with the clothing style all copied by his companions, made him the laughing stock of the local population. And General Sommerville, the tax collector in Galveston, ....was heard laughing...when he saw how the prince’s attendants were dressing him, and how two were needed to pull the pants of the Most High guest over his noble limbs! For his part, the prince wrote that Sommerville was a drunken bore and a scoundrel — just one example of his rather low overall opinion of America and Americans. From San Antonio Solms made two expeditions with Bourgeois and Ducos, several surveyors, and an armed guard: first to the Medina grant and then to a tract south of San Antonio that might augment it. Both trips were marked by arguments with Bourgeois, whom the Prince termed “arrogant, like a Frenchman.” Each man accused the other of being afraid of the Indians. There were other difficulties, as described in Solms’ diary: August 6: Rode along the line of hills on the Medina where it is closest to the Quihe. [Bourgeois] said that there were ‘wonderful lakes,’ That is, water holes without water; therefore we went back to the Medina.... Red bugs en masse.... Fell out of the hammock when a dry branch broke. August 15: In the evening we camped along the San Antonio. There was nothing to eat. Only warm water to drink. We started a prairie fire. It burned all around us.... We had no gunpowder. I had only two bullets in my pistols. August 16: We rode in a southwesterly direction to the confluence of the Cibolo and the San Antonio. Couldn’t find a trail. Why? Because there is none. Solms admired the Medina region but judged that all the good land had already been claimed. He reported to Germany that the grant was not viable, and relieved Bourgeois of his Colonial Director position. The Frenchman was not happy and filed a claim against the Society along with a report of his own in which he accused the prince of waste and extravagance. Back in San Antonio, the Prince decided to celebrate Princess Sophie’s birthday by having his cannons fired in her honor: [Aug. 9, 1844] The Germans cheered. Everyone [else] thought those were the Mexicans [invading]; a few swam across the river, others came running out of their houses with their pistols. Things calmed down. |

The Prince's wardrobe  The Bourgeois-Ducos Grant  A “red bug” or chigger  The Medina River |

|||

|

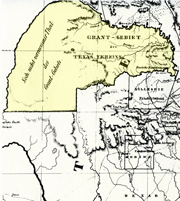

Now the prince shifted his attention to the Fisher-Miller grant. He soon learned that this new tract was too far from the coast to be settled immediately, and that most of it lay within Comanche hunting grounds. Solms rather naïvely reported to headquarters that he would force the Comanches into a peace treaty or deal them a crushing military defeat. He requested that the Society send “as many settlers as possible” by March of the following year.

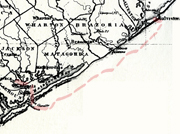

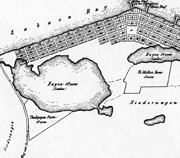

The month of September was spent at Nassau Farm planning and assembling staff, making another fruitless trip to the capital, holding target practice, socializing, drinking Rhine wine and champagne, and reading Goethe and Schiller. Meanwhile the Verein’s first charter ship, the Johann Dethardt, sailed from Bremerhaven with its cargo of immigrants, to be followed closely by three more ships. Together the passengers would comprise the first party of settlers. In mid-October Solms journeyed to Galveston to begin preparations in earnest. He fumed at having to wait nine days for Fisher, the land-grant holder and his new right-hand man, to arrive. He engaged D. H. Klaener to be the Society’s agent there. The plan was for Klaener to receive the new immigrants and transport them to a camp on the mainland, where Solms would purchase land for a supply depot and warehouse. Fisher was to secure oxen, horses, and wagons for transport. The prince did not want his Germans to have any contact with the scurrilous locals, so rather than rely on existing routes and stopping points he envisioned a series of isolated camps or way stations along the Guadalupe River between the coast and their destination. Solms and Fisher planned to scout the route and then explore the land grant with a group of Texas rangers led by Major Jack Hayes. But for reasons unknown, Solms and Fisher did not scout the route, nor did they ever get to the grant. Instead they returned to Nassau Farm via Houston, where the prince held consultations with his staff, sent dispatches, and was briefed on the assembling of provisions and livestock. In mid-November he and his ‘entire company’ departed for the coast to meet the first shipload of immigrants. From Port Lavaca Solms rather belatedly set out by boat to explore Matagorda Bay for suitable land for a debarkation camp and storehouse. When he finally reached the island of Galveston December 2, he found that the Johann Dethardt had arrived ten days earlier. After waiting for him in vain, the 120 settlers aboard, including Wilhelm Reuter, had been ferried to Lavaca, some 150 miles to the southwest. They were taken inland from the bay to a wooded area with a creek, where they made camp in tents issued by the Verein . There they would remain for a month, waiting for the prince and his officials to organize the next stage of their sojourn. They received food every eight days from the Verein storehouse in Lavaca; the men went hunting to supplement their diet. Otherwise there was little to do. Prince Solms — ever an impressive sight in his royal regalia — finally arrived at the immigrant camp December 12. The German arrivals, unlike the skeptical Texians, treated him with deference and awe. The prince immediately heard complaints about their shoddy treatment aboard ship, and noted that the settlers were already quarreling among themselves. Brought face to face with the reality of more than 100 people camped in the wilderness, at the mercy of the elements and wholly dependent on his judgment, Solms realized that the time for reports, conjecture, and awaiting instructions from headquarters was over. He hastened off to purchase land at Indian Point and lay out the harbor settlement he christened Carlshafen (after three Carls in the Society, including himself), where future Verein immigrants would make camp in the coming weeks and years. Weighing heavily on the Prince was the need to make a much larger land purchase where he could settle his colony until the difficulties associated with the northern grant could be overcome. He set his sights on Las Fontanas (the fountains), an “excellent and beautiful place” he had heard about 30 miles from San Antonio that was said to have good land, wood, and water. But even this location lay some 160 miles from the coast. Solms’ immediate task was to move his settlers inland while protecting them and providing for their needs. |

The Fisher-Miller grant  Galveston in 1846  Henry Francis Fisher  Galveston to Matagorda Bay  Carlshafen, later Indianola  Las Fontanas: the Comal tract |

|||

|

Christmas came just as the immigrants from the fourth ship arrived in camp. There were no evergreens, so a native oak tree was decorated after the German fashion with lighted candles. The prince distributed presents to the children. Rev. Ervendberg, the recently hired pastor, conducted services on Christmas Eve. A full moon shone down on the two immigrant camps that night.

On January 1, 1845, the colonists began their trek inland. They joined forces at Agua Dulce, or Chocolate Creek, 12 miles from the coastal camps. There were almost 300 people, of whom 128 were men. Now failures in logistics became painfully apparent. Fisher had been given $13,000 in Germany to purchase supplies, provisions, and livestock for transportation. But he had bought only 18 yoke of oxen and 18 wagons and paid double the market price. He had failed to budget for the purchase of corn for bread or the slaughter of beef. Supplies that he said would last six months were already nearly depleted. In short, Fisher had run through the money with little to show for it. He was taken to task by the prince and other Verein officials. The prince quickly created an organization, drawing heavily on his military background. He placed military men in key posts, including that of accountant/treasurer, and devoted much attention to forming a militia and volunteer reserves. He designated a ‘Colonial Council’ that met periodically to take up problems and make decisions. Its members were Nicholas Zink, Engineer; (ex-Lieutenant) Jacques von Coll, Accountant and Chief Military Officer; and Theodore Koester, Medical Doctor. Reporting to von Coll were the Chief Wagoner and several other officers in charge of military training, artillery, the border patrol and the volunteer militias. The border patrol consisted of 20 young men who were salaried, given room and board, and decked out in fine uniforms with high boots, velvet collars, and cockade hats with long black feathers. They wore swords in rather anachronistic European fashion. A second group of trained volunteers was recruited to join the standing militia in case of emergency. The prince also planned to train all the men in camp in the use of weapons on Sundays. Prince Solms remained at the Agua Dulce camp for almost three weeks, during which time he held three colonial council meetings, promulgated military articles and camp regulations, and inspected the militias. During that brief period of camp life a child died, the doctor and treasurer fought a duel, a wedding took place, and the ox drivers got drunk and caused a row. The prince rode ahead to inspect the trail and next camps, then spent the next month in Industry and Galveston. |

The Prince's Christmas tree  Chocolate Creek  Dr. Theodor Koester |

|||

|

Zink and von Coll were given the task of moving the settlers from one newly established camp to the next: Trailor’s Farm, then Victoria. Their route roughly followed the left bank of the Guadalupe River. Always they camped in the wilderness, well away from existing towns. They traveled by oxcart or wagon or on foot. Settlers with means purchased a horse or pony to ride. In Victoria the shortage of wagons brought the company to a standstill. Engineer Zink had three forges set up in camp and hired blacksmiths to make 14 two-wheeled carts. He also rented more wagons from local farmers. The reinforcements allowed half the group to reach McCoy’s Creek, 84 miles inland, by late February. By this time the settlers had already been living in tents for two to three months.

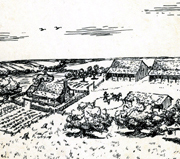

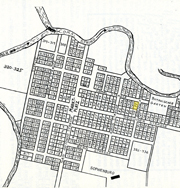

Prince Solms joined them there to conduct business and inspect the company. Matters with Fisher came to a head at a heated council meeting, where it was resolved to buy Fisher out of his contract and have no more dealings with him. The prince wrote: “After all these days...my first impression of him has proven correct: he is a scoundrel.” He was also critical of various staff members. He suspended the doctor, observing that “Dr. Koester...has neither knowledge nor experience as a Doctor nor does he have any common sense as a person. He looks at the whole enterprise as if it were a comic opera...to be used for the acquisition of as much money, provisions, wine, and cognac as possible.” Other officials he termed “malicious” and “uncouth.” Solms rode off again, this time to San Antonio, to buy the tract of land. He purchased two leagues at the confluence of the Guadalupe River and Comal Creek, for the sum of $1,111.00, from landowners Juan Veramendi and Rafael Garza. Upon inspecting the land he described it in his diary: On the right bank of the Comal Creek, which flows through it, lies a fertile prairie which reaches south to a ridge of hills. On its left bank there is a richly wooded bottom land stretching to the cliffs, which are covered with cedar, oak, and elm. These cliffs, with the hills rising gradually back of them toward the north resemble the Black Forest. Through the bottomland flows the Comal River, which, gushing out of the rock in seven large springs, shortly reaches a width of twenty paces, and becoming larger and larger, rushes along like a swift mountain stream. Its water is very deep and clear as crystal. The prince immediately set out for Seguin, where he met up with Zink, Coll, and an advance party of thirteen men. They reached the Comal tract on March 18. It was bitterly cold; a norther brought snow. They inspected the land and cut a four-mile trail to the spring. Meanwhile the hardier settlers had made the 68 miles to the Comal in two weeks via Gonzales, King’s Farm, and Seguin. It was March 21, 1845 — Good Friday — when the first immigrant wagons forded the Guadalupe and halted on the east bank of Comal Creek. Among the 200 people present that day at the founding of New Braunfels was Wilhelm Reuter. The remainder of the group arrived in the days and weeks to come. The settlers were told that New Braunfels was a temporary settlement where they would stay for a year or two until enough Germans had arrived to withstand the Comanches in a move to the larger grant. In the meantime those in this first group would receive a free gift of land in New Braunfels as recompense for the delay and for the extended amount of time they had spent in the wilderness due to the Society’s lack of organization. The first order of business was protection — they were after all at the edge of the frontier. Patrols were established and palisades erected, with the prince noting, “What a chore it is to get the people to work!” Engineer Zink surveyed the land and laid out the half-acre town lots and 9 1/2-acre farm lots. The numbered lots were drawn out of a hat and distributed by April 5. The settlers set to work building temporary or permanent shelters and cabins. They had to start from scratch, cutting and hewing logs; many were inexperienced at such work. They were hampered by rainy spring weather, and by a lack of food other than meat and game, which was in plentiful supply. The temporary storage shed had a leaky roof, and much of the food stored there spoiled, including four wagonloads of corn. The Society had plans for public buildings, but all the able-bodied men were busy building their own dwellings. Although a few turned their earliest attention to preparing their farm lots and planting corn and potatoes, most would not harvest a crop that year and many did not bother. They expected the Society to continue feeding them. Many colonists were unhappy not to be taking possession of the 160- and 320-acre tracts specified in their Verein contracts. Some were vocal in their dissatisfaction and criticism, while others resigned themselves to life in New Braunfels, channeling their energy into their new farms or establishing trades. Whether they realized it or not, they were the fortunate ones. |

The long trek inland  Traveling by oxcart  Comal Creek  Snow in the hill country  The Guadalupe  Nicholas Zink  New Braunfels town lots of 1845 |

|||

|

On April 28, with much pomp and circumstance, Prince Solms laid the cornerstone for his proposed fortress on Sophienburg Hill, named for his fiancée. He raised the Austrian flag and fired another cannon salvo. Most of the settlers were dismayed at this display and held their own ceremony. They raised the Texas flag in the plaza, convinced that their future lay with the Republic and its probable annexation to the United States, rather than with the country they had left behind. Two days later the Prince officially christened the town New Braunfels. Within a month he had left the fledgling colony for his princess and castle in Germany, never to return to Texas.

The prince took about 70 letters from the colonists to friends and family in Germany, which he mailed in Mainz. At least 13 of these letters — all containing glowing descriptions of the writers’ new lives in Texas — were transcribed by the Verein and distributed to German newspapers in an effort to recruit more colonists and combat recent criticism that the Society had been negligent in its treatment of the colonists. The letters apparently had their desired effect. Thousands of Germans flocked to sign on with the Verein. Prince Solms left in his wake a near-insolvent organization in financial chaos. The prince, the engineer, the treasurer, Fisher, and various agents of the Society had all been spending money and incurring debts, with no apparent concern for a budget or any means of accounting. Von Coll, the accountant and treasurer, was more interested in his military duties than his financial ones. In short, no one had assumed fiscal responsibility for the enterprise. Now its creditors began to lose patience. The New Commissioner-General |

Republic of Texas flag  Braunfels Castle |

|||

|

Baron Otfried von Meusebach, a young Prussian nobleman, student of law and geology, and accomplished civil servant, came from a family with the highest tradition of literary culture, political liberalism, and noblesse oblige. Taken with the dream of freedom and democracy, he gave up a life of security, comfort and success to become both a Texan and the new Commissioner General for the Society. Upon leaving Germany he renounced his noble title. Henceforth he would be known simply as John O. Meusebach.

While still in Germany, Meusebach studied public records of the Society’s activities and funding level and surmised that it must be approaching insolvency. Count Castell assured him that the princes would never let that happen, and gave him a line of credit for $10,000 to take to Texas. But Castell concealed from the new commissioner his own dire assessment that the organization was nearly bankrupt. Upon reaching New Orleans Meusebach learned for the first time of Fisher’s business manipulations. In Galveston he learned of the prince’s miscalculations and waning popularity; in Carlshafen he saw firsthand the poor conditions that greeted the new arrivals. In each new location Meusebach was presented with outstanding bills from creditors. When he got to New Braunfels he was dismayed to find that the prince had already left for Germany. A cursory look at the books showed him that the Society was $20,000 in debt. The new commissioner hastened to Galveston to catch up with the prince, who was eager to see him as well: the Society’s creditors had obtained a writ of attachment causing Solms to be detained there. Meusebach was forced to use most of the $10,000 line of credit to pay off those creditors and the ones the prince would face in New Orleans. He sent along to headquarters in Germany his stark assessment of the Society’s financial condition, along with an urgent plea for money to cover outstanding debts. Back in New Braunfels, Meusebach had to piece together a set of books incorporating the hundreds of promissory notes that had been issued. He moved quickly to tighten financial controls, setting up a system of bookkeeping and limiting the number of officials allowed to sign drafts. He was deeply troubled by the Society’s precarious financial situation. The initial funding of $80,000 had been used up; debts now amounted to $24,000, while obligations to feed and supply the settlers in New Braunfels continued on a daily basis, quite apart from the huge outlays that would be needed for future settlers. Meusebach feared that if other Verein officials in Texas learned of the true state of affairs they would become disheartened, and that if the colonists found out there would be a general panic. He resolved to keep his knowledge to himself and to project an air of confidence to the people and the Society’s creditors alike. |

John O. Meusebach  The von Meusebach family crest  Meusebach's ledger of Verein debts |

|||

|

Meusebach did not agree with the prince’s views on German separatism, nor did he find the colony’s military culture appropriate to the new world. He issued an invitation to Americans to settle in New Braunfels, believing that they would bring pragmatism and useful frontier experience to share with the Europeans. He dismantled the prince’s military hierarchy and turned von Coll’s militia, with its cockaded hats and clanking sabers, into a work regiment — prompting von Coll to resign.

Three months passed and no funds arrived from Mainz. Meusebach wrote, “There is exactly ‘0’ (zero) in the treasury. ” There was so little cash that officials had to take a collection to pay for letters to be sent by messenger. The commissioner had another major consideration: the Verein was sending more immigrants who would need land. He resolved to go to the Fisher Miller grant to see if it could be settled, pressing Fisher to accompany him. The latter dropped out of the expedition after 60 miles, while Meusebach and a few companions continued to the nearest border of the grant, 150 miles from New Braunfels. He confirmed the presence of hostile Indians and the absence of any non-native settlements in the intervening areas. Clearly the grant could not be occupied yet. On his return trip Meusebach camped in an idyllic valley near the Pedernales River, 75 miles northwest of New Braunfels, and decided it was the perfect location for the next intermediate Verein settlement, to be called Fredericksburg. He purchased the land on credit. After two months in the wilderness, the commissioner returned to New Braunfels, expecting to find enough funding from Germany to continue the Society’s operations. Instead two envelopes were waiting: one bearing the news that over 4,000 new immigrants were en route to Texas; the other a bank draft for $24,000 — barely enough to cover outstanding debts. He also found a restive population. Before leaving Germany, many colonists had deposited their savings with the Verein , which had promised to act as a bank and issue their funds upon demand in Texas. Now the settlers were unable to withdraw their own money. Not only were there no funds to disperse, but the records of deposit had not even been conveyed to Texas — in fact these records would not reach New Braunfels until the following spring. Other colonists continued to complain bitterly about not getting more land. Some refused to make provision for themselves, claiming it was the Society’s responsibility to care for them. There was nothing Meusebach could do except issue reassurances and encouragement. His most pressing concern were the thousands of new colonists arriving on the coast, whose numbers exceeded the entire population of west Texas. He had no money to feed, transport, or house them. Some few were brought to New Braunfels using existing wagons and the labor of settlers who owed money to the Society. The rest had to huddle in Galveston and Carlshafen in miserable conditions. |

Jean Jacques von Coll  Comanche warrior  Landscape near Fredericksburg  New Braunfels in 1847 |

|||

|

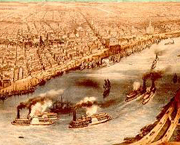

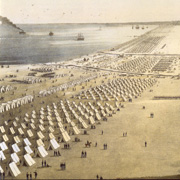

Alwin Sörgel arrived aboard a Verein ship in February 1846. He found 700 Society immigrants stranded in Galveston, housed in three large wooden buildings or boarding in the town at their own expense. They had been waiting four weeks or longer for ship transport to the mainland. In Carlshafen there were 2,000 more, some of whom had been there for over three months. They lived in a few wooden structures, “built hastily,” in tents, or in the open.

Desperate to help these unfortunate ones who had placed their trust in the Verein, Meusebach dispatched a messenger to the Society’s banker in New Orleans, M. Lanfear, asking for a bank draft; but Lanfear, acting on ‘strict’ orders from headquarters in Germany, rejected his request. By this time Meusebach, who was not drawing a salary, had used up all his personal funds. He could easily have declared the Society in Texas bankrupt and dissolved it, to his own personal advantage — his contract called for financial indemnification in such an event. But he cared deeply about both the venture and the human beings involved. He also considered his personal honor, and that of the organization, to be at stake. He traveled to Galveston — a three-week trip due to flooded roads — and saw firsthand the wretched conditions of the new arrivals. He sent a fresh budget to Mainz detailing the urgent need for $140,000 to care for the new immigrants. In a last-ditch effort, he set out for New Orleans to make a personal appeal to Lanfear, this time offering Nassau Farm as collateral for a loan. The banker’s refusal was a devastating blow. The princes in Germany had proven oblivious to every appeal. The commissioner knew of only one way to get their attention: the German press. In February 1846, he met with Klaener, the Society’s agent in Galveston. Klaener too was desperate; it was he who had to deal with the arriving masses. He had already mortgaged his own property to secure what funds he could. Meusebach asked Klaener to write a letter detailing the true conditions and suffering of the immigrants — something he in his position as commissioner could not do. Klaener’s letter to the mayor of Bremen appeared in major German newspapers and had its desired effect of finally loosening the nobles’ purse strings. It also caused them acute embarrassment and displeasure. A credit of $60,000 was dispatched by special messenger, but it did not arrive in New Braunfels until September 1846. Had that same amount been sent a year earlier when it was first requested, the disaster to come might well have been averted. |

Alwin H Sörgel  New Orleans ca. 1850 |

|||

|

In December 1845 Texas joined the United States, permanently dashing the princes’ dreams of a German colony. By this time the U.S. army was already stationed in Corpus Christi, near the Mexican border. Now the army requisitioned all available wagons and draft animals to move its troops into position for the coming war with Mexico. The proximity of Carlshafen to army movements created competition for food and supplies that would continue for the duration of the war (May 1846 – February 1848), the same time period of most Verein arrivals.

The winter of 1846 was one of the rainiest in memory. Roads became impassable. Rivers and streams flooded, cutting off communication between the coast and the inland. All hopes for transporting the settlers faded. There was not enough food in the coastal camps. Disease set in and spread rapidly. Of the several epidemics that raged, the most deadly was spinal meningitis. It came to New Braunfels in the spring when some of those stranded were finally moved, and to Fredericksburg after the establishment of that colony in May. There it was misdiagnosed as scurvy, leading to more unnecessary deaths. The coming of warm weather only increased the spread of the disease. Estimates of the number of deaths range from 800 to 1200. A long shed was built on the outskirts of New Braunfels to serve as a hospital, and an orphans’ home eventually followed. 1846 was a year of terrible crisis and tragedy for the Society in Texas and for it commissioner. Thousands of colonists were living in wretched conditions, desperately ill, or dying. They became hopeless, disillusioned, and angry. There was little Meusebach could do, with his creditors’ notes selling at one fourth of their face value. Only through personal ingenuity, skillful persuasion, and unceasing energy was he able to secure any of the needed food and supplies. |

General Zachary Taylor's forces at Corpus Christi  Disease and desperation  1846 was a terrible year for the immigrants |

|||

|

One bright spot was the founding of Fredericksburg. In April 120 settlers left New Braunfels in wagons, arriving on May 8. Other groups followed. By the end of the year 500 immigrants had come to the new settlement to claim their allotment of land — although almost 100 of them died in the epidemic.

The arrival of funds from Germany in September — still less than half the needed amount — finally allowed those colonists with funds to withdraw them. But it did not quell the discontent. An angry mob, whipped up by the scheming of certain Verein officials, burst into Meusebach’s office and threatened to hang him. He faced them down calmly. Other Germans and Americans in New Braunfels immediately came to his support. But the incident precipitated Meusebach’s decision to resign his post. Before he did that he wanted to ensure that the colonists’ land claims in the Fisher Miller tract were secure. The contracts for those claims, issued by the Republic of Texas, would lapse on September 1, 1847, if the Society did not have the grant surveyed. But no surveyors or agents would agree to go into the area for fear of the Comanches. Meusebach believed the only option was to make peace with the Indians. In January he set out for the grant with 40 wagons and some hunters. Just across the Llano River he was met by Chief Ketemoczy, who agreed to assemble the other Comanche chiefs to hear his peace proposal at the next full moon. Meusebach then dismissed his entire company except for seven men and Major Robert Neighbors, an Indian agent who was considered an expert at making treaties. The meeting was held on the lower San Saba. Meusebach promised $3,000 worth of gifts in exchange for the Comanches’ promise to allow the surveyors to do their work, and not to harm German colonists. The chief wanted to know what the white men’s intentions were; if they were to do battle it was agreeable to him. Meusebach replied that they came as neighbors extending hospitality from the two towns he represented, and wanted the same hospitality and integrity from the Comanches — with no treachery and no horse stealing. |

Fredericksburg  The Protestant church at Fredericksburg  A Comanche chief |

|||

|

Ketemoczy invited the commissioner’s party to the Comanches’ central camp at the next full moon to continue negotiations. Several hundred warriors were massed on one side, the women and children on the other, with the three main chiefs in the middle. Meusebach rode up and down the line of warriors and, in an act of trust, emptied his firearms into the air, as did his aides. He then sat with the chiefs and negotiated the agreement. A peace pipe was smoked and he was given the name El Sol Colorado after his red beard. He invited the Indians to Fredericksburg for a celebratory feast.

Except for a few minor incidents of horse stealing, the Comanches kept the treaty. They never molested white men within the boundaries of the grant or attacked the German settlements, although they continued to engage in ferocious raids farther south. As soon as the peace treaty was concluded, the surveyors entered the grant and carried out their task. Texas subsequently granted 1,735,200 acres to Verein colonists. But most of the immigrants never occupied the tracts whose shining promise had brought them to Texas. When Meusebach’s peace expedition was finally able to explore the San Saba and Colorado land, they found the soil too poor for farming and the region not well suited for settlements. The colonists sold their deeds to speculators. Wilhelm Reuter sold his 320 acres for $100 in May 1854; by November it was resold for only $32. One of Meusebach’s final acts as commissioner was to site the first settlement within the Fisher-Miller grant. The colony of Bettina was established by 40 idealistic German university students, who planned to run it based on principles of brotherly love and voluntary common effort. The Verein directors in Germany gave the group a $12,000 stake and held high hopes for them: “an elite group with capital and competence...instead of the earlier peasants.” The ‘elite group’ melted away a year later when their funds ran out and they were expected to work. That was the end of Bettina. Of the five settlements ever established within the Fisher Miller grant, only one, Castell, survived. The Society’s denouement was marked by intrigue spanning the Atlantic. Phillip Cappes, a special envoy sent by Count Castell to investigate Society affairs, secretly worked to discredit Meusebach and blame him for the organization’s failures while hoping to be appointed in his place. Meanwhile the colonial director in Fredericksburg, ‘Dr.’ F. Schubbert, was found to have a fraudulent identity, dubious credentials as a physician, and extravagant appetites that he freely indulged with Verein money. When Meusebach fired him, Schubbert conspired with Cappes. In Germany Count Castell, desperate to save his personal reputation in the face of increasing public censure, encouraged Cappes in his schemes. In the end Castell abandoned Cappes, while Society directors saw through the envoy’s denunciations of Meusebach, voting instead to commend him for his extraordinary service. A member of the commission investigating the Verein’s failures laid them squarely at the feet of Count Castell. By mid 1847 the Society was still heavily in debt. Continued operation would require a large infusion of capital and skilled leadership in Texas. With Meusebach’s resignation, the princes in Germany gave up on the enterprise and began the process of liquidation. Fisher reappeared and reorganized the Society as the German Emigration Company, but failed to breathe new life into it. The company limped along until 1853, when it assigned all of its rights to its creditors. |

Meusebach's treaty with the Comanches  Comanche lookouts  Land in Llano county |

|||

|

John O. Meusebach settled on land near Fredericksburg, raised a family and lived a rich private life until his death in 1897, fulfilling the motto he had added to his family coat of arms: “Texas Forever.”

The Society failed in its effort to create a new Germany in Texas. It failed its colonists miserably — even criminally. It did not deliver on its most basic promises, failing to provide thousands with sustenance, shelter, tools, supplies, or ‘good’ land. It withheld immigrants’ personal financial assets to cover its own indebtedness. Worst of all, it left thousands stranded to sicken and die. The Verein’s failures cannot be attributed to greed or even callousness on the part of its noble directors, as many critics charged at the time. They were rather the result of the nobles’ utter lack of business sense or experience, their naïveté, and their failure to trust their own officers in Texas, combined with fraud and intrigue perpetrated by various land speculators and certain Society officials. Although the Society for the Protection of German Emigrants in Texas failed in its eponymous task of protecting its settlers, it did bring almost 10,000 German immigrants to Texas. Through hard work and industry, most of them eventually found a way to make a living; many became quite prosperous. New Braunfels and Fredericksburg flourished. Verein immigrants also fanned out to live in other cities and towns and to found a number of new settlements. And they wrote to their relatives and friends back in Germany extolling the relative freedom and opportunity of their new land. In the decades that followed, the flow of German immigration to Texas increased. The 1860 census showed a significant minority of Texans claiming German ancestry. To this day the city of New Braunfels celebrates its unique story and German heritage. The Sophienburg Museum and Archives in New Braunfels preserves the rich history of the Society through its museum exhibits and vast collection of papers and letters. © Julia Moore, 2015. All rights reserved. Related Stories: Wilhelm Reuter German Emigration in the Nineteenth Century The Voyage of the Johann Dethardt New Braunfels Sources: Biesele, Rudolph, The History of the German Settlements in Texas, German-Texan Heritage Society, 1987 Fey, Everett Anthony, New Braunfels: The First Founders, Eakin Press, Ausin, Texas, 1994 Von-Maszewski, Wolfram M., ed., Voyage to North America 1844-45, Prince Carl of Solms’s Texas Diary of People, Places, and Events, German-Texan Heritage Society and University of North Texas Press, Denton, Texas, 2000 King, Irene Marshall, John O. Meusebach, German Colonizer in Texas, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, 1967 Von-Maszewski, Wolfram M., ed., A Sojourn in Texas, 1846-47, Alwin H. Sörgel’s Texas Writings, German-Texan Heritage Society and Southwest Texas State University, San Marco, Texas, 1992 |

John Meusebach in later years |