|

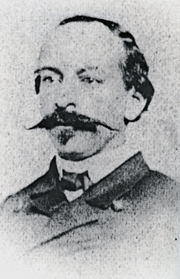

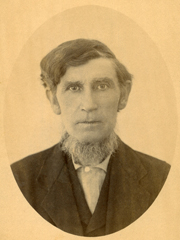

Henri Castro was a flamboyant French entrepreneur who dreamed of achieving great wealth by selling Texas land to European immigrants. He became a land grant ‘empresario’ and attempted to colonize the area west of San Antonio that later became Medina county. There he established the towns of Castroville, Quihi, and D’Hanis. Our ancestors John Heyn Heyen and Antje Dirks were among Castro’s earliest colonists in Quihi. Other ancestors later settled in or near both Quihi and D’Hanis.

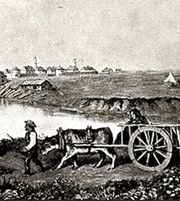

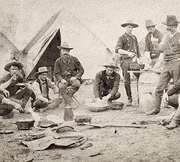

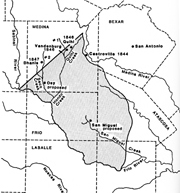

In the early 1840s, the Republic of Texas hoped to attract European immigrants to populate and secure its frontier areas. To this end, it granted large tracts of land to a few empresarios, who were to recruit settlers and fully settle the grants within three years. In return the empresarios would gain title to half of the land for their own use. The empresarios’ main motive was profit, and most of them turned out to be unscrupulous to some degree. Castro, who had a background in finance, secured a 1.25 million-acre grant on the Medina River near San Antonio, as well as a 600-acre tract on the Rio Grande. (The latter grant was never settled because of the threat of war with Mexico.) Castro set up an emigration company headquartered in Paris, taking personal charge of recruitment efforts. With his confident, stylish manner and impressive command of English, he attracted a number of French and Alsatian colonists. Castro guaranteed the prospective settlers only a plot of land; they were required to provide their own passage, tools, and sustenance. The empresario contracted space on ships to the Gulf Coast and provided the emigrants with a set of detailed instructions, including train schedules, hotels, needed supplies, and contacts in Galveston or New Orleans. But Castro had no organization or agent in Texas. Once the immigrants disembarked they were on their own. By early 1843 Castro had sent 96 leaderless colonists to Texas, many of whom had little money, no concept of the Texas frontier, and no farming experience. Upon landing they were dismayed to discover they had to make their way 150 miles inland to San Antonio by foot or oxcart over rough trails. ‘Coastal fever’ (malaria or dysentery) frequently took its toll during the overland journey. Those who made it to San Antonio found they could not take possession of their land — which lay 50 miles to the west — because of the prevalence of Indians, bandits, and Mexican soldiers. They were forced to find accommodations in the half-empty Hispanic town, or to camp along the river in unhealthy conditions. There they suffered for over a year in abject poverty. Alarmed by the colonists’ desperate situation, the French foreign minister denounced Castro and attempted to bar him from signing up new colonists in France. Castro quickly moved his operations away from Paris, recruiting instead in Alsace, Switzerland, and Germany, where he found willing takers. The new emigrants also made their way to San Antonio. In May 1844 Castro finally departed for America aboard the steamship Caledonia. By coincidence, Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels, Commissioner General for the Society for the Protection of German Emigrants in Texas, was on the same ship with his retinue. He was Castro’s chief rival in the emigration society business. The two men apparently ignored each other for the duration of the passage. Later that summer the prince would note in his diary the wretched condition of Castro’s would-be colonists in San Antonio, and distribute alms to them in honor of his fiancée’s birthday. This would infuriate Castro, who would accuse Solms of attempting to bribe his colonists away to the Society’s venture. When Castro finally arrived in Texas to take command of his operation, he was met by angry crowds in both Galveston and San Antonio. Somehow he managed to rally a small band of 27 intrepid souls to found the town of Castroville on the Medina River. The settlers built primitive homes with thatched roofs and began trying to farm the land. Wary colonists trickled in, but the settlement grew slowly. That same year Castro surveyed the future settlement of Quihi, about ten miles to the west on Quihi Creek. Castro hired Louis Huth, a Swiss, as his manager in Texas. Huth was hard-working and capable, and the operation took on more order. It was March 1846 before Huth established the town of Quihi with some twenty-four families. Quihi’s founding was marred by the massacre of a family who had strayed too far into Indian territory. A few months later Huth led 50 families to settle Vandenburg, about five miles away on Verde Creek. Castro’s agents recruited a handful of colonists from Ostfriesland in the northwest corner of Germany, near the departure port of Bremerhaven. They included Mimke Mimken Saathoff, his second wife Antje Dirks, and their children, including Antje’s 15-year old son John Heyen. The colonists from Ostfriesland joined the fledgling settlement of Quihi in September 1846. By this time Castro had overextended himself and was in severe financial straits. He secured a sizable investment from a Belgian consortium headed by Guillaume D’Hanis, but was forced to concede a good deal of control over his finances — on paper at least. Castro sited his last settlement on the Seco Creek, 25 miles west of Castroville, and named it D’Hanis after his financier. Castro’s grant bordered the frontier. The Texas government was glad to have his settlements as a buffer between San Antonio and the hostile Indians, bandits, and Mexican soldiers to the west. In 1849 the state established a ranger camp on the Seco Creek to protect the D’Hanis area. It became Fort Lincoln. Most of Castro’s colonists were too poor to own farming implements, horses, or guns. Without tools they had to clear the land and plow it by hand. Without guns they were unable to hunt game for food. In Quihi the Texas Rangers shot game for the new settlers. But progress was slow. The poor quality of the soil and the lack of access to water also hampered the growth of Castro’s settlements. The land was better suited to grazing than farming; many would-be farmers turned to raising stock after futile efforts at crops. In 1847 the term of Castro’s land contract expired, which meant no new settlers could receive land. Of the 2,000 immigrants he had brought to Texas, only 500 to 600 lived in one of his four villages. The others had settled elsewhere on the way to the grants, returned to Europe, died of disease, or joined the U.S. Army to fight in the Mexican war. Castro proved to be an unscrupulous businessman who failed to fulfill his promises to his colonists, his creditors, and even his loyal employee Louis Huth, who had exhausted himself and his resources to further Castro’s interests. Castro’s venture devolved into lawsuits and recriminations. Despite several legal judgments against him, Henri Castro managed to retain a great deal of land and to live out a comfortable life in Texas. The villages of Castroville, Quihi, and D’Hanis all survived, stabilizing in the early 1850s — just as Verde Creek dried up, leaving the residents of Vandenburg without water. Many of them moved a few miles downstream to establish the settlement of New Fountain. Vandenburg was abandoned. The religious preferences of the towns in Castro’s grant reflected the geographic origins of their respective settlers. Catholics predominated in Castroville (France and Alsace) and D’Hanis (Bavaria and Württemburg), while Quihi (northwestern German states) was mostly Protestant, with a Lutheran church. A German circuit rider came to New Fountain and founded a Methodist church, finding receptive parishioners who had grown up in Reformed rather than Lutheran regions of Germany. A number of families from Quihi became members of the New Fountain congregation. Other settlers from Ostfriesland joined the pioneers in Quihi in the 1840s and 1850s. Among them were Schweer Balzen and Zeda Heyen, who arrived in 1855 with their four children. David Detlev Schluentz and Christine Elizabeth Schade came from Holstein in 1854 with two surviving daughters. D’Hanis and Fort Lincoln became the closest towns to Wilhelmine and Wilhelm Reuter when they bought ranch land on the Seco in 1853. And Matthias Richter and Christina Armbrust brought their family to a ranch near Fort Lincoln in 1854. © Julia Moore, 2015. All rights reserved. Related Stories: German Emigration in the Nineteenth Century Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas Sources: Weaver, Bobby D., Castro’s Colony, Empresario Development in Texas, 1842-1865, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, Texas, 1985 The History of Medina County, Texas, Dallas, Texas, National Sharegraphics, Inc. Von-Maszewski, Wolfram M., ed., Voyage to North America 1844-45, Prince Carl of Solms’s Texas Diary of People, Places, and Events, German-Texan Heritage Society and University of North Texas Press, Denton, Texas, 2000 |

Click on pictures to enlarge

Henri Castro  Empresario land grants in Texas  Traveling by oxcart  Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels  Castroville in the 1840’s  John Heyn Heyen  Seco Creek at the site of Fort Lincoln  Texas Rangers  Castro’s home in Castroville  Castroville in 1850  Castro’s grant and towns  Heyo Schweers house in Quihi |

|||

|

|