|

All of our ancestors came to America from Germany between 1844 and 1883. They left behind their way of life, their families and friends, their homes and villages or cities, knowing they would never see those people or places again. Those ten families were part of a massive tide of German emigration in the 19th century that totaled almost 5 million souls.

The conditions in Germany that led to this exodus were the result of severe economic, political, and social displacements that gathered steam in the first half of the century and reached a crisis point in the late 1840s, when the great surge in emigration got underway. The century began with the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), which devastated much of Europe. Massive armies — both French and Allied — marched through broad swaths of the countryside, seizing wealth (see Martin Wilhelm Reuter’s story), spreading disease (see Eleanor Wenzel’s story), and living off the local population. Napoleon defeated Austria in 1805 and Prussia in 1806. The French victors imposed harsh financial burdens and high tariffs, and began to reform the German states’ administrations, centralizing them on their own model. After Napoleon’s subsequent defeat in Russia in 1814, the other European powers rallied and rejoined forces, finally marching into Paris and forcing the emperor to abdicate. At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the borders of Europe were redrawn. Gone was the Holy Roman Empire, which had survived for more than 1,000 years, and with it the old German Empire. The other European powers wanted to prevent a strong, united Germany from emerging. They devised a weak confederation of 35 (later 40) separate states, kingdoms, and city-states, known as the Deutscher Bund or German Confederation. Prussia and Austria were the largest kingdoms; Bavaria, Saxony, Württemberg, Hesse, Baden, Hannover, and Holstein were sizable entities; and the remaining 23 were small or tiny. Each state had its own ruler, laws, and policies. Thus ‘Germany’ did not exist as a country until 1871. It became a concept in the minds of those who identified themselves as German, and a fervent ideal for those who dreamed of a unified state. Our ancestors who left at mid-century actually came from the kingdoms of Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Hannover, Hesse, and Baden. The decades of war left in their wake a crushing burden of debt and heavy taxation. Conscription imposed an added burden on common people, since each German kingdom maintained a standing army to defend its borders. The ruling governments in Germany, which had promised reforms as a way to rally support against the French, went back to their conservative, repressive ways, while they continued to centralize power. The war-weary populace seemed content for the most part to turn inward and enjoy two unprecedented decades of peace in Europe. During this period, known as Biedermeier, the virtues of home and family became a German ideal, as did the accompanying bourgeois values of thrift, tidiness, Gemütlichkeit, and uprightness. Music thrived. Beethoven, Schubert, and Mendelssohn composed Hausmusik, or chamber music, which perfectly suited the trend toward private gatherings in homes. But political discontent seethed among university students and members of the liberal bourgeoisie, who had not forgotten the recent promises of constitutional government and German unity. They organized and demonstrated. The German states responded with ruthless suppression and harsh new measures in 1819, forcing such movements underground. At the same time, unprecedented demographic changes brought about a permanent shift in the economic order. The populations of Prussia and Saxony virtually doubled between 1816 and 1865; the other German states were not far behind. By the 1830s there was simply not enough food, farmland, or employment to support the population. In the same decades industrialization was restructuring all aspects of business and trade. Trade guilds steadily lost ground to the increasingly centralized power of the states. Master craftsmen who previously could earn a good living began to live on the edge (e.g. Carl Gottlob Wiederänders), while the chances for apprentices or journeymen to ever reach the level of master, or even to make a living, fell dramatically. For the first time, large internal migrations took place, with people moving from impoverished rural areas to more prosperous rural areas or cities. The phenomenon of pauperism, or mass impoverishment, arose, and no one had a solution to the problem. By 1840 overflowing poorhouses had become a fixture in most cities. While these trends grew steadily in the early decades after the war, they exploded in the 1840s. Poor harvests in 1846 and 1847 led to famine and hunger revolts. Prices for consumer goods collapsed, affecting wealthier businessmen as well as workers and tradesmen. The desperate economic conditions fed political discontent. Sporadic student and liberal uprisings in the 1830s and early 1840s had been met with imprisonments and police surveillance. Now bitterness, anger, and demands for political reform spread to nearly all classes of society. In 1848 the overthrow of the last French king in Paris triggered revolutionary uprisings throughout the German states. In Cologne 5,000 citizens took to the streets to demand a constitutional monarchy, basic civil rights, and better conditions for workers. They were men and women, rich and poor, factory owners and laborers, intellectual liberals, moderates, and conservatives, and radical workers’ groups. Many other German cities followed suit. Barricades sprang up and there was fighting in the streets. Berlin saw an open revolt against the Prussian king. The rulers at first seemed to capitulate, promising parliamentary assemblies and reform. But the ‘Revolution of 1848’ soon fizzled in the face of internal disagreement, the moderates’ fear of the radical agenda, and Prussian might. Its perpetrators fled the country or were arrested and punished harshly. Its supporters were left deeply disillusioned or embittered. The Promise of America |

Click on pictures to enlarge

German emigrants boarding a ship for America  Surrender of the town of Ulm to Napoleon’s forces  Europe in 1815  The German Confederation  Biedermeier ideal of family life  The industrial revolution  Crowds outside a workhouse  Poverty and industrialization  The 1848 Revolution, Berlin |

|||

|

Against this background of hardship, repression, and discontent stood the possibility of starting over in America, with its cheap land, higher wages, and freedom.

A number of Germans had already done so in the 17th and 18th centuries. Many had gone by way of Holland, fleeing religious persecution. After the wars ended in 1815 the modest flow resumed. The emigrants were motivated by a desire for economic or social betterment, or perhaps by a characteristic Wanderlust, that centuries-old Germanic tradition dating back to tribal times. Their numbers swelled in the 1830s. The vast majority of those who left went to America, settling primarily in the mid-Atlantic or the Midwest. Letters from America trickled back home, some with fabulous accounts of success and wealth to be had for the taking. In the difficult years of the 1840s, individuals from all walks of life began to consider emigration seriously. Some debated the patriotism of leaving the Fatherland, with most reaching the conclusion that conditions in Germany were so hopeless as to release them from any continued loyalty. Policymakers, journalists, and merchants also began to discuss organized large-scale emigration as a way to solve economic and social problems. One proposal was to send large numbers of the impoverished to colonies in America in order to improve conditions for those who stayed in Germany. Some communities may actually have financed the deportation of their poor. Others wanted to ship out criminal elements. Emigration became a hotly debated topic. The German state governments took varying stances on the issue. Some states encouraged emigration while others, such as Bavaria, opposed it and placed hurdles in the path of those wishing to leave. All German states required young men to complete their obligatory military service or buy their way out of it. |

An American landscape  German emigrants in Hamburg | |||

|

Emigration societies arose as a way to assist those who wanted to leave — or to fulfill a political agenda. Disappointed radicals formed the earliest of these after failed political efforts. In 1833 the Giessen Emigration Society recruited 500 members to create a “new Germany” in Missouri. They set out in two separate parties, both of which were plagued by delays, disease, unscrupulous travel operators, and their own inexperience. Many abandoned the expedition en route; only a few colonists ever reached Missouri. Another group planned to assemble enough settlers to form a new U.S. state and ship it wholesale to America. That effort failed, as did the attempts of numerous other dreamers.

In the 1840s a group of princes and noblemen lent their prestige and capital to a venture that did succeed in bringing large numbers of Germans to America — but at a great cost in human lives and suffering. The Society for the Protection of German Emigrants in Texas set its sights on Texas as the ideal place for a new German homeland. Texas |

|

|||

|

A few intrepid Germans had made their way to Texas by 1840, establishing small settlements in Washington, Fayette, and Austin counties northwest of Galveston. A favorable letter from one, Friedrich Ernst, appeared in a book about Texas in 1834. Somehow the territory of Texas, with its vast stretches of unclaimed land, managed to capture the German imagination. Das Kajütenbuch (The Cabin Book), a novel about life in Texas in the 1830s, painted a vivid portrait of an enchanting land, with larger-than-life characters whose penchant for freedom and dignity was set against the territory’s David and Goliath-like struggle for independence from Mexico. Published in Germany in 1841, it crystallized the Texas mystique and became an immediate bestseller.

At the time, the Republic of Texas wanted to sell land to European immigrants as a way to finance and populate its economically struggling new nation, and also to settle frontier areas between established Texas towns and threats from Indians or Mexican incursions. In 1841 and 1842 it offered ‘empresario’ land grants similar to the ones Mexico had formerly offered in the territory. The contracts contained the provision that the land be surveyed and fully settled within three years. A handful of British, French, German, and Belgian entrepreneurs secured large grants. These empresarios, or agents, stood to receive up to half the land in question as compensation for their efforts. Their motive was profit, and they competed with each other for advantage. Three empresarios and their grants played a role in our ancestors’ stories. Henri Castro, a Frenchman, obtained a sizable grant on the Medina River. Armand Bourgeois, another Frenchman, held the Bourgeois-Ducos grant bordering Castro’s grant on the Medina. And Henry Francis Fisher, a German, had a contract for the much larger Fisher-Miller grant to the north. |

Empresario land grants in Texas |

|||

|

In 1842 Henri Castro set up an emigration company in Europe to recruit colonists for his land. He eventually founded the towns of Castroville, Quihi, and D’Hanis. At first Castro didn’t bother to establish an organization in Texas. He sent several hundred colonists over but provided them with virtually no support. Most of the immigrants were without means and totally unprepared for the conditions they encountered. They were left stranded, unable to occupy the land they had been promised. Many suffered and died. In 1844 Castro arrived in Texas, established the town of Castroville, and laid out Quihi. He belatedly hired an agent in Texas to manage operations. But the land itself was poor and did not support farming, and his settlements grew slowly. Castro overextended himself financially and resorted to unscrupulous actions. His venture ended in debt and lawsuits.

Antje Dirks and John Heyn Heyen were among Castro’s original colonists in Quihi in 1846. The Schweer-Balsen family from Ostfriesland joined them there in the 1850s, as did the Schluenz family from Holstein. And Wilhelm and Wilhelmine Reuter and Matthias Richter bought ranches near D’Hanis in the early 1850s. Other land empresarios preferred to sell their contracts rather than recruit their own settlers. The newly formed Society for the Protection of German Emigrants was the perfect sales target. The ambitious noblemen backing the organization required a large tract of land for the German colony they planned to establish in Texas. They had ample resources and little concept of the topography of Texas or actual conditions there. Armand Bourgeois and Henry Fisher vied to sell their respective land rights to the princes. Fisher eventually won out, and it was a 160-acre tract of his grant that the Society promised to Wilhelm Reuter when he signed up in 1844. The Society recruited thousands of German emigrants with unrealistic promises of land and logistical support, which it proved unable to fulfill. It sent them off to Texas, only to discover that the Fisher-Miller grant lay deep in Comanche territory and could not be settled. The earliest colonists — the fortunate ones — founded the towns of New Braunfels and Fredericksburg and received small tracts there, but those who followed had nowhere to go. The undercapitalized venture ran out of money to feed and house them. Subsequent waves of immigrants ended up stranded on the coast at the mercy of weather and disease; some 800 to 1200 perished, and many more became gravely ill or destitute. The Society managed to continue its operations on credit and promises for years. It finally ended its existence mired in debt. Despite its failures, the Society succeeded notably in advancing German immigration to Texas. Between 1844 and 1850 it brought almost 10,000 immigrants to Texas — something of a critical mass. It founded two thriving settlements on the frontier of west Texas that became magnets for other German immigrants. Perhaps most significantly, Texas became well known throughout Germany as an attractive destination for would-be emigrants. Most of the Society’s surviving colonists were eventually able to establish farms or trades in Texas. They relished the freedom of the new world, the relative ease of living, and the warm climate. And they sent letters back to relatives urging them to pack up and move. Books and pamphlets were published in Germany that provided detailed instructions and realistic information about the amount of capital needed, necessary tools and supplies, provisions to take for the crossing, and preferred areas to settle. Between 1847 and 1861 Germans flocked to Texas in great numbers. By 1860 the German population of Texas numbered about 35,000, or 7% of the total white population. Among those who came to Texas in the wake of the Society’s and Castro’s activities were the Tips (1848-9), Richter (1854), Schluenz (1854), Schweers (1855), and Wiederänders (1855) families. Of our ancestors who left Germany at mid-century, only one family did not go to Texas. Carl Heinrich Trautsch and Joanna Hoelzer settled in Wisconsin in 1853. Although economic conditions in Germany improved in the 1850s, emigration continued to increase as more and more success stories flowed back from America and the political situation at home failed to improve. The hardships of the trip lessened over the decades as transportation systems gradually improved, with a better network of German railroads, more frequent transatlantic sailings, larger vessels, the advent of steamships, and lower fares. The Civil War slowed the flow temporarily, but it resumed in the postwar period to reach an all-time high in the 1880s. That was when the last of our ancestors crossed the ocean. Richard Beyer came to Dubuque, Iowa, in 1883, soon earning enough money as a cabinet-maker to bring his wife Augusta Dieterich and their children to join him. Augusta’s mother Henrietta Grewatz and her brothers came at the same time. The Germans in America |

Henri Castro  Prince Solms of the Society for the Protection of German Emigrants  Comanche warrior  Early settlers in New Braunfels  German Texans  A nineteenth century steamship |

|||

|

The 5 million Germans who came to America in the 19th century were the largest ethnic group to immigrate during that period; they comprised 27% of all immigrants. The vast majority settled in the Midwest. In 2000, Americans of German ancestry accounted for 35-47% of the population in six of those states.

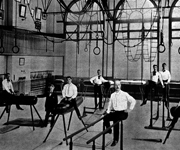

Prior to the Civil War, many Germans came to America seeking land to work, whether or not they had been farmers in Germany. This was the case for nearly all of our ancestors in the 1840s and 1850s. Land ownership in the old country was a privilege few could attain. Land was simply unavailable there, and any small family holdings had been subdivided into tiny pieces as they were handed down through generations. Carl Gottlob Wiederänders, a skilled master craftsman, yearned for “a little piece of land” in Texas that could sustain his large family. Wilhelm Reuter, an actuary and merchant, had bigger ambitions for a ranch in Texas. With the exception of Edward Wiederanders, all of our ancestors arriving in that period became (or married) farmers or ranchers in the first few generations here. German farmers tended to cluster in settlements, both in the Midwest and Texas. They built churches and schools in the small towns that sprang up. Both kept language and culture intact and attracted new immigrants. The availability of land allowed sons to acquire neighboring farms. German farmers generally relied on family labor and avoided debt whenever possible. They were socially and politically conservative, and their lives often centered on the local church. Their rural self-containment allowed them to continue speaking German into the fourth and fifth generations. In 1870, 27% of Germans working in America labored on farms — about 4% of all agricultural workers in the country. By 1900 this share had risen to 10%, with Germans owning 11% of American farms. Even in 1950, German-Americans remained the single most numerous immigrant group in agriculture. As land in the U.S. became less available after the Civil War, fewer agricultural workers and more skilled craftsmen or unskilled workers arrived from urban areas in Germany. They tended to settle in cities, as did the Beyer and Grewatz families in Dubuque. By 1890, 40% of German immigrants lived in cities with populations larger than 25,000. Assimilation occurred more quickly in urban areas. Still, in cities with large German populations — New York, Milwaukee, St. Louis, and other Midwest cities — Germans maintained their identity and sense of community through churches or clubs. Clubs included lodges, mutual-aid societies, volunteer militias, and groups formed around interests such as gymnastics, debate, or drama. Singing societies were popular at all levels of society. In the 19th century there was a gulf between the ‘church Germans,’ who tended to be pious, conservative, and family-oriented, and the ‘club Germans,’ who were often more liberal, educated, and secular. Germans’ ethnic identity in America resulted from their shared values and lifestyle, with the family ever at its center. The rural concept of family as a joint economic enterprise had its urban counterpart in small-scale family enterprises. In either case women worked alongside the men, and children left school early to work, either for the family or as domestic servants or apprentices. As a family’s status improved the focus shifted to a middle-class ideal of a small, closed family circle held together by the bonds of love and duty. Always the father held dominant authority and the wife and children had subordinate status. The sentimentalized ideal of home, family, and patriarchal authority stemmed from the Biedermeier period in Germany, where it had assumed an equally important role in defining German identity. German culture in America was also defined by a social component that centered on enjoyment and conviviality. Germans were enthusiastic about their picnics and feasts, their Sunday strolls, their dances, music and songs. A glass of beer, wine, or schnapps was mandatory. Taverns and beer gardens abounded in German neighborhoods, the latter being places where the entire family could relax together. Germans’ celebratory bent was sometimes at odds with the dominant culture’s blue laws, temperance societies, and later Prohibition. Through the end of the 19th century, Germans were able to maintain dual loyalty to their roles as American citizens and members of an ethnic subculture with at least sentimental ties to the old country. World War I brought to an end to their easy identification with their ethnic culture and language. With war raging in Europe, the German-American press and some political groups lobbied for U.S. neutrality and against aid to the British. This stance was seen as anti-American by many of their countrymen. Woodrow Wilson exploited anti-German sentiment in his 1916 campaign. The U.S. entry into the war in April 1917 unleashed a torrent of activity against ethnic Germans by local government-sponsored “defense committees.” Harrassment included a ban on music by German composers as well as the renaming of certain towns and foods. It escalated to vandalism, arrests, tarring and feathering, and even a lynching in Illinois. German books were routinely collected and burned. About half the states prohibited German-language instruction, and some even outlawed the speaking of German in public. In Cedar Falls, Iowa, after the local defense committee listened to one of Carl A. Wiederanders’ sermons dealing with original sin, it summoned him to a hearing in which he was accused of being unpatriotic, and was insulted and threatened. The result of the widespread harassment was a decline in German-language publications, the dissolution of certain ethnic associations, and a rapid shift to the English language in churches and schools. At least publicly, German-Americans preferred to sacrifice their ethnic heritage for the sake of their status as American citizens. And their searing experience in the First World War inoculated most, if not all, against the greater menace to come. When the Nazi party attempted to gain German-Americans’ support in the 1920s and 1930s, it was roundly rejected. Increased mobility and educational opportunities in the 20th century reduced the ethnic identification and relative insularity of German communities and sped assimilation. This trend is reflected in our own ancestry, where the near-universal practice of marrying a German-American spouse with roots in one’s own community gave way in the 1940s. © Julia Moore, 2015. All rights reserved. Related Stories: Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas Castro’s Colony Sources: Sheehan, James J., German History 1770-1866, Oxford University Press, New York, 1994 Thernstrom, Stephen, Ed., Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, Harvard University Press, 1980 Biesele, Rudolph, The History of the German Settlements in Texas, German-Texan Heritage Society, 1987 Weaver, Bobby D., Castro’s Colony, Empresario Development in Texas, 1842-1865, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, Texas, 1985 The History of Medina County, Texas, Dallas, Texas, National Sharegraphics, Inc. |

German population density in the U.S.  Threshing in the 1870's  Rural church in a midwestern German farming community  A brewery in Dubuque  City life   Christmas Eve in a German family  Beer garden in the early 1900’s  Anti-German poster, World War I   Hugo Schweers and Mimmi Richter in 1916 |

|||

|

|