|

Martin Wilhelm Reuter came of age during a time

of momentous change and upheaval in Europe. In

the second half of the 18th century, the feudal

society based on land-owning aristocracy,

serfdom, and the power of the trade guilds began

to lose ground, while a new “educated elite” (whose ranks Martin would join)

of non-noble bureaucrats

and professionals was emerging. The Bastille fell

in 1789, when Martin was 18. The French Revolution

ignited populist hopes and fervor throughout the

continent, but soon plunged all of Europe into

war and economic chaos.

The Reuter family had lived for generations in Schweinfurt, a small but proud Reichstadt, or Imperial City. Martin's father, Johann Georg Reuter, was a baker and member of the city council. Martin attended the Latin school and the classical Gymnasium (secondary school), and studied jurisprudence at the Universities of Jena and Erlangen from 1790-93. In the summer of 1796, when French troops overran Schweinfurt, he was a 25-year-old attorney. |

Click on pictures to enlarge

Martin Wilhelm Reuter, Bürgermeister, oil painting by Conrad Geiger, 1801 |

|||

|

The French demanded a war chest of 500,000 pounds

from the city, an astronomical sum. To guarantee

payment, they seized eight prominent citizens,

including Martin's father. The French were

persuaded to exchange the five older detainees

for their sons, and thus it was that Martin

Reuter found himself on a coach bound for

imprisonment in Givet, France, near the Belgian border. Back home, the

citizens of Schweinfurt endured the enemy

occupation and agonized over their gallant sons

languishing in that gloomy hilltop fortress.

They needn't have worried. The very civilized French garrison commander offered his young prisoners fine food and wine, elegant clothing, even the latest French literature. The hostages rose to the occasion. They entertained the general, his charming wife, and his aides in grand style, and outfitted the shoemaker who had accompanied them as a liveried servant. Indeed, they seem to have spent a most pleasant and educational time in captivity. |

18th century Schweinfurt  The Fortress of Givet (at upper left on the hill) |

|||

|

After 11 months the tide had turned, a truce

was signed, and the hostages were released. They

were not, however, in any great hurry to tear

themselves away from “sweet France.” En route home, they took an

extended gentlemen's tour, sightseeing in France

and Germany, spending and tipping lavishly at

inns and taverns along the way, and buying gold

watches and finery for their wives and lady

friends. Only the more sober heads among them

dissuaded the little band from making an additional detour to

Paris.

With great rejoicing the townspeople of Schweinfurt prepared a heroes’ welcome. On July 29, 1797, the hostages were met by the city fathers and escorted into Schweinfurt by the Austrian garrison and a 30-coach procession. The entire town turned out to greet them, waiting for hours at the city gates. Cheering citizens lined the streets and hung from upper windows. Nine young maidens in flowing gowns and garlands sang a song especially composed for the occasion, and danced with the youthful heroes at an official banquet. Prayers and hymns of thanksgiving were offered in church, and the town council ordered gold medals of honor to be minted in Nürnberg that would commemorate the loyalty and suffering of their native sons. |

Handbill advertising the song for the returning hostages |

|||

|

Inevitably, the day of reckoning arrived. The French had

been billing the hostages’ living expenses in

Givet to the city of Schweinfurt. The town

council now requested an accounting. When the

scandalous details of their extravagant

expenditures came to light, the townspeople were

shocked and outraged. Overnight, the hostages

went from heroes to disgraced scoundrels.

The citizens demanded that their profligate

outlays be repaid.

It was wartime, after all, and those at home had been enduring hardships and an enemy occupation. Meanwhile, what the hostages spent on new clothes alone was more than a military officer's annual pension. All in all, their bill totaled about 14,000 guilders — an amount equal to half the city's entire revenue in the year 1805. The city council quickly cancelled the order for the gold medals and appointed an investigative commission — to an unenviable task, since the culprits were the sons of the town's leading citizens. Finally the commission censured the hostages “strenuously,” but forgave their “unnecessary outlays” as recompense for service to the Reichstadt. Despite their youthful indiscretions, the men had in fact stepped forward on behalf of their city in a time of need. All in all, the scandal brought shame to the hostages, who probably looked back upon the experience as something to be lived down rather than a golden adventure. The youths returned from France to difficult times. The war raged on, while the economic and political situation deteriorated. In 1802 Schweinfurt lost its prized status as an independent Reichstadt and was annexed by the kingdom of Bavaria — a difficult blow for the citizenry. |

The eight hostages of Givet |

|||

|

Martin Reuter continued his legal practice and was elected to the City Council, becoming counsel to that body in 1801. From 1814 to 1818 he served as

Second Bürgermeister (Deputy Mayor) of Schweinfurt. He

reportedly became extremely conservative —

perhaps in an effort to compensate for his

youthful extravagance — eschewing any new or

progressive ideas. (A contemporary historian

referred to him as “a man

of the prior century.”)

His portrait, painted by a prominent

artist of the time, hangs in the City Museum

today.

Martin's first wife, Wilhelmine Noltenius, died in 1806 following the birth of their only son, who also died. In 1807 Martin married Maria Uhl, the daughter of a local merchant. The couple had eight children, of whom four sons and two daughters survived infancy. All were well educated. Son Wilhelm spoke both French and English. At the time of his marriage to Maria, Martin lived in House #323, currently Stadtknechtsgasse #6. By the time Wilhelm was born, the family had moved to House #299 (currently Marktplatz #33), which is directly on the main marketplace. Both dwellings are within a stone's throw of the Rathaus where Martin conducted his legal and government business. He was now a prominent citizen of comfortable means. By 1842, the year he died at age 71, Martin had seen hard times and the industrial revolution alter the landscape and social structure of Schweinfurt. His sons were leaving the town of his ancestry for opportunities elsewhere. Maria Reuter died at age 61 in September, 1845, from a fever that also claimed her youngest daughter Mariana Theresia, who was 28. That year Wilhelm, 25, had just arrived in Texas. The Reuter family house and estate in Schweinfurt remained in probate for over a year because Wilhelm could not be located to supply a power of attorney for the settlement. Martin’s four sons all left Schweinfurt. In 1845, Gustav was residing in Bamberg, while Emil, the youngest, lived in England. Caroline Reuter, the oldest daughter, never married and remained in Schweinfurt until her death in 1899. © Julia Moore, 2006. All rights reserved. Sources: Kirchenbücher records from St. Johanneskirche, Schweinfurt Böhm, Wilhelm, “Die Gieseln von Givet, Ein Finanzskandal in Alt-Schweinfurt,” Schweinfurter Mainleite, Nummer 1, February 1993, Historischer Verein Schweinfurt. “Blick auf die benachbarte Stadt Schweinfurt um die Mitte des 19. Jh,” by Leonhard Friedrich Enderlein, from 75 Jahre Oberndorf-Schweinfurt: Bauern und Fabrikarbeiter; edited by Rolf Schamberger, Schweinfurter Museumschriften Heft 62/1994, Stadtliche Sammlungern Stadtarchiv Schweinfurt, 1993. Letters from Gustav Reuter and Caroline Reuter, Solms-Braunfels Archiv, New Braunfels, Texas Sheehan, James J., German History 1770-1866, Oxford University Press, 1989. |

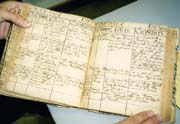

The Rathaus, or City Hall, where Martin Reuter worked  The housefront on Stadtknechtsgasse where the Reuters lived  Kirchenbuch containing the records of Reuter family births and deaths |