|

The earliest record of “Villa Suinfurt,” a small fishing settlement on the Main River in the gentle hills of Franconia (northern Bavaria), dates from 740 A.D. In the ensuing centuries, the town’s fine harbor and strategic location — at a ford over the river where major north-south and east-west routes intersected — made it a constant target of attacks by powerful and ruthless rulers of surrounding territories. One such seige totally destroyed the city in 1250.

To protect itself, Schweinfurt sought and eventually attained (in 1282) the elite status of freie Reichstadt, or Free Imperial City, which allowed it to govern itself under the sole authority of the Holy Roman Emperor. Reichstadt status afforded any city unparalleled political autonomy, including sovereign authority over its own municipal laws, local elections, churches, police and military forces, taxation, and education. The 100 or so Reichstädte in the Empire included large, wealthy cities like Augsburg and Frankfurt as well as very small cities of quite modest means like Schweinfurt. Thus Schweinfurt had from medieval times onward a tradition of self-governance by its Bürgershaft, unlike many of the nearby townships that were under the feudal governance of a prince, duke or bishop. In 1802, following the French invasion (the setting for the infamous hostage episode involving Martin Reuter as a young man), and general political upheaval throughout Germany and Europe, Schweinfurt was forced to give up its free imperial status and become part of Bavaria. The citizenry of Schweinfurt prospered throughout pre-industrial times from commerce, fishing, farming, wine-making, and other trades. The 19th century brought rapid and expansive change to the town. Cotton mills, iron foundries, and factories that produced paint, soap, liqueurs, sugar, malt, shoes, and machinery transformed the city and its suburbs. Today Schweinfurt is a bustling industrial city of 55,000 people. Although much of the city was destroyed during World War II, many of its oldest and loveliest structures were left standing in the Altstadt, or Old Town. Overlooking the Marktplatz or Town Square (where twice-weekly markets have taken place for centuries), stands the Rathaus (City Hall), built in 1572. Here several ancestors carried out their duties as members of the Rat, or City Council. Martin Reuter eventually achieved the office of Second Bürgermeister (second mayor) — one of four Bürgermeistern in the 16-member “inner council” of the Rat from whose ranks the Oberbürgermeister, or Lord Mayor, was chosen. Martin’s father, Johann Reuter, and his wife’s grandfather, Johann Uhl, were both members of the Achterstand, or Council of Eight advisory citizens, part of the “outer council.” The Reuter family attended the St. Johanniskirche (St. John’s Church), which dates from the 13th century. Records of generations of births, marriages, and deaths were kept there in the Kirchenbücher (church books). In 1542, following the Protestant Reformation, Schweinfurt made the Evangelical-Lutheran faith its official denomination. This decision had political ramifications, as Schweinfurt was located between the powerful Catholic bishoprics of Bamberg and Würzburg. In the bloody Peasant Wars that followed the Reformation, Schweinfurt was twice occupied; then plundered, burned, and totally destroyed for the second time in its history. The city offered asylum to many Protestants seeking shelter from religious persecution in the predominantly Catholic territories of Franconia. This in turn led to a fresh influx of economic and intellectual life in the late 16th century and to heightened prosperity for the town. Religious tensions finally erupted in 1618 in the Thirty Years War, which devastated much of the German countryside but left Schweinfurt relatively unscathed. Both Martin Reuter and his sons (including Wilhelm) studied Latin and other classical subjects at the Gymnasium Academicum. Built in 1582 as a Latin school, it became the first upper school, or Gymnasium, in the region in 1634. Johann Fichtel, Martin Reuter’s maternal grandfather, was Gymnasiuminspektor and Alumnor there (Supervisor, Dean, or Headmaster) in the mid-1700s; he was also a Pastor and Cantor at the church. Today the Altes Gymnasium is a museum housing Schweinfurt’s municipal collection, where Martin Reuter’s portrait hangs in a gallery of works by the Geiger family of painters. Daniel Reuter, the earliest Reuter ancestor for whom we have records, was born in nearby Oberndorf and came to Schweinfurt prior to 1695. He was a farmer and freeholder. Among other Schweinfurt ancestors were several pastry bakers, another landholding farmer, a grocer, a merchant/trader, and a mill-scribe. Schweinfurt in the Mid-1800s |

Click on pictures to enlarge

Schweinfurt from the Main River  The two-headed eagle, symbol of the Holy Roman Empire  A fresco in the City Hall of a record-size fish caught in 1593  The Rathaus (City Hall)  Lord Mayor’s palanquin  St. Johanniskirche  The Altes Gymnasium, formerly the Latin School |

|||

|

The following impressions of Schweinfurt are excerpted from an account written in 1836 (when Wilhelm Reuter was a teenager) by Friedrich Enderlein, a recent arrival who was used to a more cosmopolitan existence:

Schweinfurt is a well-loved, friendly, provincial town. Its modest buildings are made of flimsy half-timbering. It lacks the tall houses and massive stonework of larger cities, except for a few main buildings and streets near the Marktplatz. The church is unimpressive, and the unpaved plaza surrounding it littered with multitudinous piles of dung. The pavement is in execrable shape except for the two streets that run between the church and the residences of the leading citizens. The few existing oil streetlamps are lit only sporadically on moonless nights in winter. Walking to the river, one sees the new gate [Brückentor] at the bridge to the city, the prison, and below it, the huge dark city mill — already an outmoded “boneshaker.” On the river, about 60 men and several horses are dragging a ship against the current through the city lock. The job takes 4-6 hours and costs 70-80 florins, plus a “lock tax” to the city. From the riverbank a scene of idyllic beauty: the Marien Brook Valley stretching to the Theil Mountains, and the old city moat, where lovely beechwood hedges separate the myriad gardens (carefully laid out to take advantage of peak blooming times) where many families while away long summer evenings together. The field near the Upper Gate [Obertor], a dumping ground for scraps from the soap works, is also used by farmers as a site for the protracted and tedious business of breeding boars, much to the dismay of Mayor Kirch, whose efforts toward beautification are steadfastly resisted. Near the Spitaltor [Hospital Gate] one finds a brickyard, a lumberyard, some new construction, and the cemetery, already nearing capacity. Numerous trading firms signal a substantial mercantile industry. Annual markets in the many surrounding villages are lucrative for a number of local families, who travel all night on loaded wagons to spread out their boutiques for the farmers. Weekly markets in Schweinfurt swell the retail business of the plaza considerably, though the stalls and shops are simple and rude. One seeks in vain elegant wares, or shop windows with attractive displays. The most prominent business in Schweinfurt is the firm of W. Sattler, Englehardt, and Co. Originally a paint and dye factory, it now encompasses a sugar refinery and new factories producing lead, Wedgwood, and carpets. Of great economic importance here is the central customs office. It is said to collect the third highest tolls in the kingdom, primarily through its collections from colonial sugar, which is refined in two refineries here; these produce over 300,000 florins in import tax. Among the citizenry one detects the residue of the “Imperial City” demeanor: they proudly refuse to acknowledge their shrinking status, and grant any official only the barest minimum of the respect or authority he merits. Social opportunities are distinctly lacking, and primarily confined to domestic gatherings. Totally nonexistent are outdoor taverns for the summer months or coffeehouses where one might stop midday. Women can only meet in their homes or gardens. There are occasional splendid evenings at certain hospitable, well-to-do homes. Anyone accustomed to the lifestyle of Munich, Nürnberg, Regensburg, Bayreuth, etc., will find no local substitute, and will therefore feel grateful to gain entry to such respectable ranks. For the young people of the educated classes, the halls of the Harmonie [concert hall] and the choral societies offer the opportunity to meet one another. The lower classes must make do with the so-called “monthly music” in the inns on the Brückengasse. One doesn’t need to be a Puritan to be put off by the uncouth activity of these exuberant peasant folk and the working class craftsmen, vine tenders, and boatmen. Already at 3 in the afternoon one hears the hooting and yelling in houses and on the streets; here and there are ejections, scuffles, and the flash of knives. Rarely does a St. Killian Day or Peter-Paulfest [warm weather festivals] go by without a dangerous stabbing. But Schweinfurt in the year 1836 is undoubtedly no better nor worse than other cities under the same demographic conditions (i.e. those with emerging factory-worker populations). People who still remember the years 1814-1816 know (from a scandalous chronicle of that time) that not much has changed. And it is not just maids and common people involved in such scandals, but names with the best sound of Mademoiselle, Madame and Monsieur. |

Brückentore (Bridge Gates)  Schweinfurt from the east, mid-19th century  “Schweinfurter Vogelschuss auf dem Bleichrasen”  Price list for the Wilhelm Sattler Factory  A Schweinfurt vintner  Schweinfurt from the south, mid-19th century |

|||

|

Religiosity seems to be in good shape, for the price of a seat in the churches commands a goodly sum. In both churches these seats [stools or pews] are almost all privately owned, and a well-situated one represents an investment of 100 florins or more. About the public school and its quality one can only be suspicious. The schoolteacher is not respected and is shut out of better society. But luckily for the local teachers, they do not have to collect monthly school fees (often requiring police assistance) and deliver them to the city treasury; for here no tuition is paid at all.

Despite the significant amount of commerce, adequate transportation and roads are severely lacking. The post goes daily to and from Würzburg, Bamberg, and Meinungen (also Kissingen in summer), with conveyance of people and parcels or packages only twice a week. Since December 18, 1829, citizen Bürgermeister Kirch has stood at the pinnacle of city government. He studied at university, though he did not receive a degree. An older man who embraces measured progress, he is always equipped with a writing tablet on which to jot his observations or complaints about the police. At his side are two Rechträtte [councilors of the law]: Reuter, an unshakeable opponent of anything new, especially if it costs money, and Cramer, a jurist of the more modern school. There are also 6 citizen magistrate councilors. The administration of justice [in Schweinfurt] is handled by the city court. The district court has jurisdiction over both the city and exempted parties [such as nobles and the clergy]; the district circuit extends to the border of Thuringia. The county court has jurisdiction over the countryside. |

Postal coach coming through the Spitaltor (Hospital Tower) |

|||

|

[Note: Friedrich Enderlein became a teacher at the Gymnasium, and may well have taught Wilhelm Reuter.]

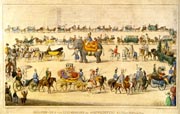

Wilhelm undoubtedly belonged to one of the choral societies mentioned above — perhaps the Liederkranz, founded in 1833, famous for its masked parades on the Schweinfurt Marktplatz. The most splendid and exotic of these took place in 1840, and included an elephant and a zebra. © Julia Moore, 2006. All rights reserved. Sources: |

“Liederkranz” costume parade in Schweinfurt, 1840 |

|||

|

“Städtische Sammlungen Schweinfurt in Altes Gymnasium,” Guide to the Municipal Collections in the Museum in the Altes Gymnasium, published by the city of Schweinfurt.

Kirchenbücher records from the St. Johanniskirche, Schweinfurt “Blick auf die benachbarte Stadt Schweinfurt um die Mitte des 19. Jh,” written by Leonhard Friedrich Enderlein, from 75 Jahre Oberndorf-Schweinfurt: Bauern und Fabrikarbeiter; edited by Rolf Schamberger, Schweinfurter Museumschriften Heft 62/1994, Stadtliche Sammlungern Stadtarchiv Schweinfurt, 1993. Zeitriese: Schweinfurt -- von der Freien Reichstadt zur Industriestadt, Verlag Ludwig & Hohne Werbeagentur GmbH, Schweinfurt, 1985. |