|

Peter Andres, our earliest known Wiederanders ancestor, was born between 1465 and 1470, possibly in Bohemia. By 1501 he was married and living in Annaberg, a brand new boomtown in lower Saxony that had been founded in 1496 following the discovery of silver ore nearby. The name of Peter’s wife is not known.

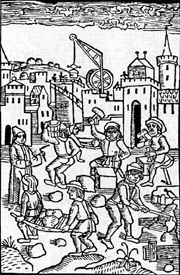

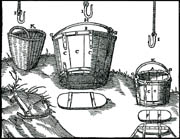

In various records Peter’s surname appears as Andres, Endres, or Enders. He was also known as Peter Buthner or Buttner, after his profession as a cooper (Büttner or Böttcher). It was his son Lorenz who first began to use the name Wieder Enders, which means “again, Enders,” or “Enders afresh.” (The phrase “Das ist wieder anders” means “That is an entirely different matter.”) Peter Andres’ other offspring continued to go by the surname “Andres.” As a maker of vats, buckets, and barrels, Peter prospered from the frenetic growth and construction of early Annaberg. A large mine works was being built, along with scores of houses, public edifices and a huge church. People were flocking to the town. Sturdy containers were needed for processing minerals, and to transport and store everything from ore to nails, water, beer, and foodstuffs. Peter also became something of a real estate speculator. By 1502 he held a mortgage on a house, and in ensuing years he bought a number of houses, which he usually sold or traded soon thereafter. He is also named as a party in several money-lending transactions. In 1518 he bought a house on Wolkensteiner Strasse (one of the main thoroughfares leading down to the marketplace), and it became the Andres family home. Over the course of his lifetime, Peter Andres participated in the transformation of Annaberg from a rough and brawling settlement to a well-organized, carefully governed society within a walled city that boasted the splendid St. Anne’s church, several other churches, a Rathaus, market square, jail, and public gallows. He witnessed the founding of the City Council, the Guard, and the trade guilds, and the beginning of traditions such as the yearly market and fair. He swore allegiance to three successive dukes of Saxony. He survived plague epidemics, and was present when enemy forces besieged the city and forced it to surrender (it was recaptured the following day). He watched people get rich from mining silver and saw them scramble when the ore petered out. He lived through the Protestant Reformation and its adoption in Annaberg. Baptized a Catholic, he was buried a Lutheran. Peter was a member of the coopers’ guild that was first organized in Annaberg in 1517. Trade guilds were an integral part of a skilled craftsman’s life and identity, and also of the commercial and social organization of the community. Guild membership was required to practice a trade at any level — apprentice, journeyman, or master craftsman. Guilds regulated the standards and terms of commerce within their trade. Self-governing, they met quarterly and collected dues from their members. They disciplined members, but also acted as benevolent societies in the event of misfortune. Guilds paid taxes to the town for the support of the schools, churches, and the protection of the city. Guild members trained each other’s sons as apprentices. Their wives and daughters organized dances and social events for the members. Families within a guild were socially close and often intermarried. Guilds staged parades or plays for the public in the marketplace, where each group would show off its own particular talents. For Shrove Tuesday revelries, the coopers would dance and perform high leaps while holding barrels above their heads. Peter’s sons were also coopers. Each was apprenticed, as a young boy, to a master craftsman to learn the craft. Apprenticeship lasted seven years and was a state of total dependence, during which the apprentice lived at the master’s establishment and was to be treated as a son. After seven years, the young man became a journeyman and had to leave his hometown to work for wages for a master cooper. To attain the status of master craftsman, the journeyman had to amass some means and pass an examination before his elders. The profession of cooper has been passed down in the Wiederänders family in an unbroken line from Peter Andres to the present time. Up until 1800, almost every male descendant of Peter Andres learned the craft of coopering as he grew to manhood. After 1800, some of them turned to other professions, notably farming and baking. Today, coopers named Wiederänders still live in Annaberg. Peter Andres had seven children who grew to adulthood:

That house was eventually inherited by Jacoff’s daughter Maria and her husband Georg Meder. She apparently died with no living heirs, for the house passed to her husband and then to his nephews, who sold it to another cooper named Dietterich in 1600. In the late 1700s, Johann Christian Wiederänders purchased the house, bringing it back into the family. Johann’s grandson Carl Gottlob Wiederänders finally sold the family home when he came to America in 1854. For centuries the house was known as Das Büttnerhaus (house of the coopers). In April of 1551, Peter Andres appeared at City Hall to swear in an affidavit that his son Jacoff had paid 8 florins to two men (who were also present) “for the burial of his parents.” Presumably this was done to give Jacoff an official claim against his father’s future estate. Evidently Peter’s wife had died, and the old man was making arrangements for her burial and preparations for his own, which he suspected would not be far off. Indeed, he died within the year, and his estate was divided among his surviving heirs in June 1552. © Julia Moore, 2006. All rights reserved. Sources: Kirchenbücher records from St. Annenkirche, Annaberg Property and inheritance records from the Stadtarchiv Annaberg-Buchholz (with many thanks to Frau Pollmer, Archivist) Jenisius, Paulus, Annaberger Chronik, edited by Helmut and Reinhart Unger, Erzbebirgsmuseum Annaberg Buchholz publication, 1994 |

Click on pictures to enlarge

Early depiction of Annaberg with St. Anne's church, ca. 1550  Workmen building the new town of Annaberg early in the 16th C.  Mining structures on the hillside near the town  Woman washing mineral ore  German coopers at work in 1586  Mineral containers, including coopers' cask and bucket  Miners working underground and hauling ore in buckets  Coin-makers in early Annaberg  The house on Wolkensteiner Strasse purchased by Peter Andres in 1518  The aged man confronts his mortality |