|

In 1492 a rich vein of silver ore was found at Mt. Schreckenberg in the dark forests of the Erzgebirge (“Ore Mountains”) on Saxony’s southeastern border with Bohemia. Thus began a wild new chapter in the Great Silver Rush that had started in the 12th century, as prospectors — erstwhile farmers, craftsmen, beggars, students, and even monks — flocked from far and wide to stake their claims and seek their fortunes, much as the California Forty-Niners would do centuries later. Within a few years the mines were generating profits, and a permanent settlement was needed.

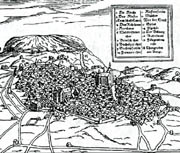

Hoping to avoid the violence and chaos that had plagued earlier boomtowns, Duke George of Saxony ordered that the new town be carefully laid out and sternly regulated, but also granted the citizens numerous privileges such as the right to travel freely, cut timber, and elect their own council and judges. In 1501 the town was christened “Saint Annaberg” to the miners’ great joy, for Saint Anne, mother of Mary, was their patron saint. Construction had already begun on a massive church, and a frenzy of building ensued. (Peter Andres was already living in Annaberg by this time.) Annaberg’s early years were stormy, full of rioting and discord between groups of miners, citizens, newcomers, and even women. Gradually law and order was established, and the Bergleute (miners) settled into a calmer existence. Since 1233, a strict and well-regarded miners’ code had governed the mining towns in the region, apportioning profits to the sovereign, the landowners, and the prospectors. An entrepreneurial spirit prevailed, for a man’s success stemmed directly from his own efforts. The difficulty and danger of the work itself, far underground, spawned camaraderie and mutual support. “Glück auf!” (“Luck up!”) was the miners’ call when they rode into the pits holding their flickering lamps, and again when they reemerged. It is still the greeting used in the Erzgebirge today. The boulder-strewn forest wilderness was transformed into a thriving, well-appointed city in a remarkably short period of time. In 1510 Annaberg boasted a population of 8,000, a Franciscan cloister, two churches, a school, hospital, marketplace, city hall, mint, corn house, bathhouse, prison, gallows, inn, and waterworks, not to mention elaborate mining structures and buildings for processing ore. By 1540 the city walls and moat had been completed, and a mercantile exchange, slaughterhouse, and malt house had been added. Wealth from the mining ventures, as well as generous contributions from Duke George, underwrote this development. Meanwhile trade guilds were chartered, and local traditions and holidays such as the yearly market were born. Seeking extra protection from their patron saint, the pious miners brought “the most beautiful stairs, ore and silver, precious stones and silver cake” to be incorporated into St. Anne’s exquisite church, which was completed in 1525 — just as the Protestant Reformation was gathering steam. Annaberg became Protestant in 1539, amid religious feuds, persecution, Counter-Reformation, and peasant uprisings in nearby towns. The citizens were left to reconcile their allegiance to the reformer Martin Luther of nearby Wittenberg, himself the son of a miner, with their loyalty to the holy saints and protectors of the old tradition that had sustained them for centuries. Around mid-century, just as the nouveau riches were beginning to flaunt their fine silk clothing, the silver ore began to peter out. Though mining continued as a staple industry for centuries, the glory days were over. It was a difficult adjustment for the proud, intrepid miners to turn to substitute means of earning a living — such as lace-making and the carving of wooden toys and Christmas decorations. The lace industry was founded by Barbara Uttman, a wealthy heiress and clever businesswoman from Annaberg, who already owned several mines and smelting plants. Before her death in 1571 she employed 900 female bobbin lace makers. (Her businesses were subjected to more rigorous audits by the authorities, who were unsettled by such a successful woman.) Unemployed miners in the region turned their inventiveness and skill with tools to the plentiful wood from nearby forests. The renowned wooden nutcracker was created, along with hosts of angels, children, folk figures, and manger scenes. The Christmas pyramid, with its rotating figures and candles, became a trademark of the Erzgebirge. The mining heritage was also commemorated in the Schwibbogen, a wooden or metal arch decorated with mining scenes and placed in windows as a welcome, and also in standing carved figures of traditionally dressed miners. In the centuries to follow, industry came to the Erzgebirge in the form of wood, paper, and textile mills and the processing of zinc, tin, and sheet metal. After World War II, Saxony became part of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), and the citizens of Annaberg were governed by a Communist regime for the next 45 years. Reunification in 1990 brought more individual freedom and greater prosperity to some, but also resulted in severe economic displacement and unemployment as underproductive Eastern Bloc industries failed. Today many young people are leaving Annaberg for jobs elsewhere, and the economic future of the town is uncertain. Annaberg in the 1500s |

Click on pictures to enlarge

Annaberg’s coat of arms: St. Anne flanked by two miners  Annaberg in the Erzgebirge  Throwing a hatchet to measure a claim in the early mining days  Annaberg miners at work in the early 1500s  The vaulted nave of St. Anne’'s Church  Barabara Uttman, who founded the lace industry  Bobbin lace-making  Wooden carving of a miner |

|||||

Annaberg was part of a feudalistic society in the 16th century. The people swore their allegiance to the Duke of Saxony, who swore his allegiance to the Prince of Saxony, who swore his allegiance to the Holy Roman Emperor. Those lieges in turn bestowed favors, certain rights, and protection upon their vassals. Duke George had a special fondness for Annaberg. In 1505 he coined this verse about “his” cities — still recited by Annabergers today:

City dwellers had considerably more freedom than the serfs who worked on the lordly estates in the countryside. But only certain Annaberg residents — including local patricians, master craftsmen, and merchants — were granted the status and rights of citizenship (das Bürgerrecht). Other groups — including journeymen and apprentices, servants, executioners, and the indigent — were excluded. German society in the 16th century was suffused with piety. The people took pride in the magnificence of the Annenkirche (St. Anne’s Church) towering over the city. As printed Bibles were few and most people illiterate, the church conveyed its teachings pictorially in 80 carved, painted stone panels that still circle the nave, depicting the Creation, the life of Christ, the martyrdom of the saints, and the Last Judgment. In addition to standard religious subjects, the artists of St. Anne’s wove depictions of local daily life into the exalted decoration of the church — providing a priceless look into life in the early 16th century. The lower panel of the staircase to the pulpit is a carving of a crouched miner hewing rocks underground. And while the front of the “Miners’ Altar” features gilded late-Gothic woodcarvings of Nativity scenes, its reverse boasts glorious paintings of the diligent miners of Annaberg at their daily work. Morality and mortality are the didactic themes of a remarkable series of carved panels on the choirloft: “The Life Stages of Women” and “The Life Stages of Men.” Every decade of a woman's life is represented by a figure in contemporary dress, from a 10-year-old girl to a 100-year-old crone, each holding a shield with a different bird on it to symbolize the personality or character development of a woman at that age — as well as the unattractive and even dangerous qualities lurking within human nature that were to be tamed by the Church’s teachings. Thus the quail stands for selfishness and inconstancy, the dove for chastity, the goose for gossiping, the peacock for vanity, etc. The parallel male figures carry shields with animals: the goat for wantonness, the bull for bellicosity, the lion for courage, the fox for deceit. The 100-year-old man and woman each carry a skeleton with a scythe, representing death. Most German towns were settled in the 13th century. Since Annaberg was a relative latecomer, its early years were well documented. The scholar and pastor Paulus Jenisius wrote (in Latin) a detailed description of town life, and kept a yearly chronicle with entries that ranged from world events to weather and crop reports, from doctrines of faith to freak accidents and the foibles of Annaberg’s criminal element. The following account is taken from his observations: The town is laid out in the propitious shape of a circle, divided into four quadrants for administrative purposes. The streets are broad and curved to thwart the wind, and paved with stones to keep the city clean. The 1,200 houses within the city walls are comfortable and well-outfitted, with gardens, open yards, stalls for animals, and root cellars. Some even have bathrooms with running water. People furnish their homes neatly and artfully, light them with tin or copper lanterns, and prize their tables made of decorative wood or marble. The German spoken here is hearty and coarse. But the Bergleute (mountain people or miners) yield to no one in cleverness. Building the mine works requires ingenuity no less than hard work: an understanding of the properties of earth, stone, and metal, as well as experience in mathematics, surveying, and mining statutes. Because they can withstand extremes of heat and cold, Bergleute make good soldiers. They are a big-hearted, courageous, responsible, friendly, amusing, talkative, and lusty people, who love generosity and despise stinginess. Social life revolves around the trade guilds, which hold regular dances and communal meals, and sometimes provide entertainment in the marketplace. The butchers put on parades and plays, the furriers demonstrate their prowess at swordplay, and the coopers dance and leap holding barrels aloft. Beer halls have been popular from the start. Here men congregate to drink, play cards or dice, and occasionally engage in fisticuffs (which are usually forgiven after another round of drinks). Social classes keep their own company; members of the Rat (City Council), for example, dine at the Rathaus and avoid congress with ordinary citizens. Weddings are the occasion for prolonged celebrations. The bride and groom seal their engagement with a handshake at a festive party. The wedding itself is preceded by three separate feasts — for the townspeople, the young men, and the maidens — and followed by two days of parties, with dancing in the house and on the street. On the third day, well-to-do families host yet another banquet, while the less wealthy eat leftovers. On Shrove Tuesday, throngs of mummers (merrymakers in costumes and disguises) stream through the streets, acting crazy, brandishing weapons, and displaying all manner of rudeness and ill-breeding. In the spring, garland-bedecked maidens with long, flowing hair dance round-dances amid strewn flowers, and sing songs containing riddles, which are solved by the young men, also in song. At New Year’s, people give their children and godparents small gifts and everyone wishes each other well. Bonuses are distributed to the civil servants, watchmen, and tower lookouts. At night people sing songs of good fortune outside of houses, hoping to receive a gift. The city walls and a system of guards and watchmen provide protection against fires, thieves, and raids. Lookouts on the towers scan the approaching roads and countryside day and night, and sound the hours and the change of mining shifts. In the event of fire, they ring the bell continuously to summon the citizens to bucket brigades. Watchmen walk the streets at night calling out the hour. Upon reports of arson or epidemics abroad, unknown persons are denied entrance to the city. There is also a local corps of [volunteer] crossbowmen and one of riflemen, who polish their skills with shooting competitions. Justice is swift and severe. Thieves, murderers, and heretics are hanged, beheaded or broken on the wheel. Two Annaberg citizens had their eyes put out by a neighboring duke for “fishing in foreign waters.” A whipping post was installed in the main church in 1535 to deal publicly with blasphemers. [Jenisius’ notes on crime and punishment are filled with local color. For example, two brothers named Gross were finally rewarded for their thievery with the noose, but they were so old they couldn’t walk to the gallows, and had to be driven there in a wagon.] Annaberg was rocked by the events of the Reformation. In 1517 Martin Luther nailed his first disputation on the doors of the castle church in nearby Wittenburg. That same year, the monk Tetzel came to Annaberg selling papal indulgences, and many people flocked to buy them. Frederick Myconius, a monk in the Franciscan cloister, was appalled by Tetzel’s claims, e.g., that he had power through the Pope to offer God’s forgiveness, even to one who had slept with the Virgin Mary — if only he would put coins into the coffer. Myconius left Annaberg and became a close colleague of Luther, writing letters of encouragement back to his hometown. In 1525 the Peasants’ War raged through the region. Rebels seized a nearby town, and an abbot who had been driven from his cloister holed up in Annaberg until the prince restored both town and cloister to the papacy. In 1530 an Annaberg monk gave a sermon about justification by faith, and was promptly imprisoned and executed. Those who embraced Luther’s reforms were persecuted, harassed, and denied burial in holy ground. A prominent schoolteacher resigned rather than submit to “the papist idolatry and arrogance of the senior pastor and his assistants.” It was not until 1539 that Annaberg became Protestant: upon Duke George’s death, his brother and successor Heinrich ordered all his subjects to espouse the new faith. Annaberg men marched under their sovereigns’ banner in numerous wars and campaigns, most notably against the Turks, who had invaded Austria. Meanwhile bands of gypsies spread throughout Europe and were feared and denounced as lazy cheaters, thieves, heathens, spies, and dogs. Floods and droughts frequently ravaged the town and ruined crops and grain. In extreme winters the river froze and the mill would not turn. Severe inflations also caused misery and hardship. Fire was a constant threat: swaths of the city were often destroyed, and several neighboring towns burned to the ground. The plague raged through the town in 1507 and many people died, including prominent citizens. It flared again periodically throughout the century, killing thousands of Annabergers. Comets were seen as portents of bad weather or other misfortune, while astrologers sought signs of impending events in the stars. Humor sustained the citizens of early Annaberg through all hardships. An example from our chronicler Paulus Jenisius: On July 30, 1560, a house was being built near the sow market. One of the workers — “a foolish buffoon but a good tippler” — fell off the roof to the street below. Fearing he might die, and hoping to revive him, people rushed to him, yelling “Water! Water, here!” But he raised his head and shouted, “No! No! Not water! BEER here!” © Julia Moore, 2006. All rights reserved. Sources: Jenisius, Paulus, Annaberger Chronik, edited by Helmut and Reinhart Unger, Erzbebirgsmuseum Annaberg Buchholz publication, 1994 Bernhard, Marianne, Die Silberstrasse und ihre Geschichte, Sachsenbuch Verlagsgesellschaft, 1992 Schulze, Hagen, Germany, A New History, Harvard University Press, 1998 |

16th century coat of arms  Citizens swearing the oath of allegiance to their lord  Carving of a miner from the pulpit base of St. Anne’s  The 40-year old man with his symbol, a lion  Map of early Annaberg  Bergleute at work  Modern day parade in traditional dress  The 20-year old woman carries a bridal wreath and her symbol, a dove  The Christmas market in the Marktplatz  The city of Annaberg and the Pöhlberg, circa 1600  The selling of indulgences  Statue of Martin Luther in front of St. Anne’s Church  The Rathaus (City Hall) on the marketplace  The Schwibbogen, with its welcoming lights: a traditional ornament in the Erzgebirge |